News that Algeria’s incumbent president, Abdelaziz Bouteflika, will not seek re-election has pushed another OPEC member into political uncertainty. Algeria’s impact on crude markets is limited and a change in laws governing hydrocarbon investment, if a result of new government, won’t necessarily lead to a turnaround in the production trajectory. However, the change of leadership does raise the share of OPEC capacity that is ‘at risk’ as a consequence of international sanctions, militant activity or untested political change.

Algeria is a relatively small crude oil producer, accounting for a little more than 3% of OPEC’s production in 2018, and output has been in steady decline for years as an onerous investment climate (stringent limits on foreign ownership and high taxes on hydrocarbon income) has deterred investment. In recent years Algeria has focused more investment on natural gas as domestic demand has been growing rapidly.

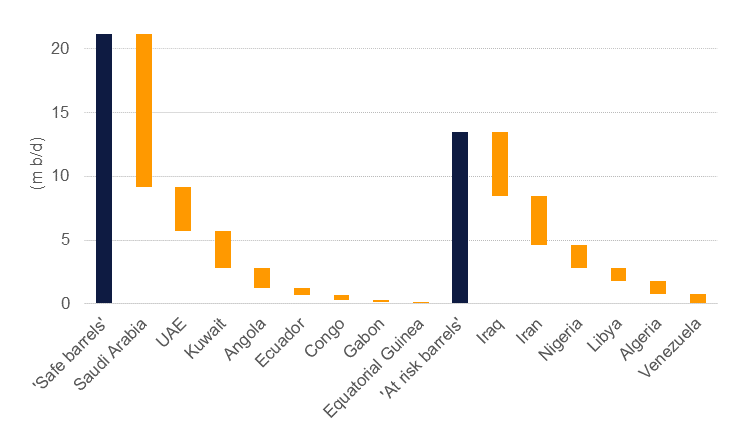

The IEA estimates that OPEC’s total capacity in 2019 is around 34.6m b/d with Saudi Arabia controlling the largest share (roughly 35% of the total). Of that 34.6m b/d total, roughly 61% are unencumbered by political risk. That leaves almost 40% of OPEC’s total output at risk. Iraq holds the largest share of these barrels at an estimated 5m b/d of capacity. While militant groups in the country have largely been defeated the risk of a flare-up is not zero and persistent debate between the central government and KRG over revenue allocation hangs over the country’s outlook.

Source: IEA, Emirates NBD Research.

Source: IEA, Emirates NBD Research.

Both Iran and Venezuela find themselves under US sanctions that will deter international investment and the Latin American nation is also undergoing profound political unrest. The IEA estimates Venezuela’s production capacity this year at just 750k b/d. That compares with production of as much as 2.5m b/d as recently as 2014. Should a political transformation occur in Venezuela it does not guarantee an improvement in the investment environment or oil production capacity even though the country holds the world’s largest crude reserves.

In Nigeria, militant activity in the oil producing Niger delta region has disrupted output in the past and the re-election of incumbent president Muhammadu Buhari may risk a resumption of fighting. Meanwhile, Libya remains riven following the end of the 2011 civil war with oil production routinely disrupted by unrest.

While these political risks affecting individual countries may not end up affecting production much they will raise anxiety about OPEC’s ability to reliably supply markets and will thus keep an underlying bid to crude prices. OPEC members that are party to the December 2018 production cut agreement are already producing 3m b/d below their collective capacity and 500k b/d of that unused capacity is held in countries where the market may discount the ability to raise output quickly.

OPEC officials in recent days have stressed that the April meeting will see no decision on the current production cuts and that the process of rebalancing markets is still a work in progress. Our expectation remains that economic conditions in key members will lead to an increase in output in H2 2019 as those with flexible capacity try to capture the benefit of higher prices and replace output impacted by sanctions.

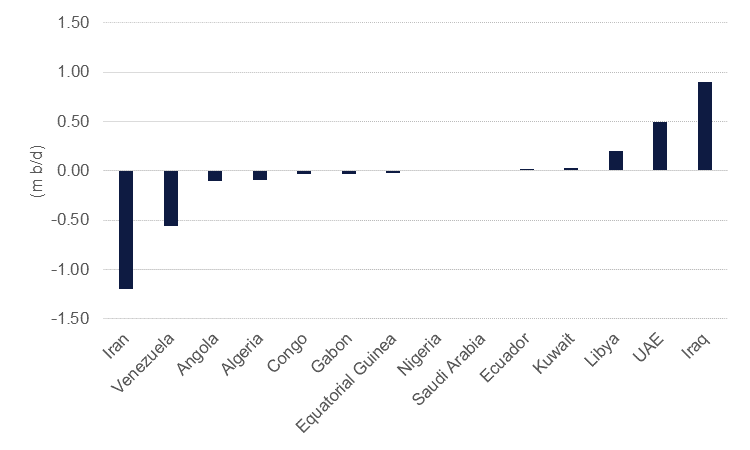

The IEA’s long-term projections expect a decline of nearly 400k b/d in total OPEC capacity as sanctions on Iran and Venezuela do long-term damage to the upstream investment climate in both countries. We would note that the forecast period provided by the IEA covers an additional election cycle in the US under which administration policy towards both Iran and Venezuela could change.

Source: IEA Oil Market Report 2019.

Source: IEA Oil Market Report 2019.

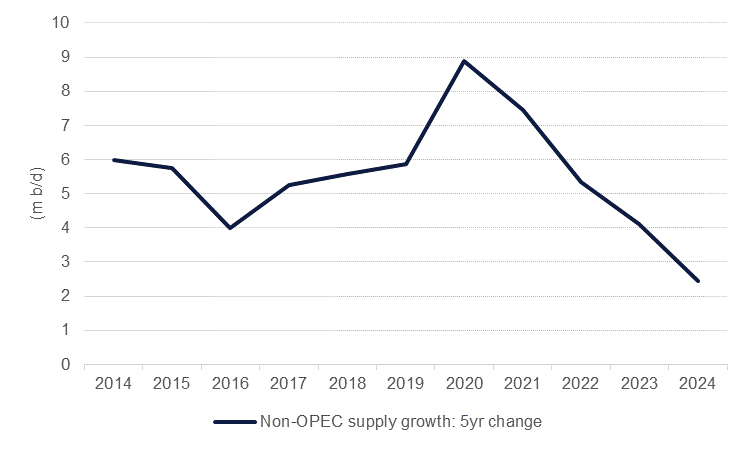

A collective sanctions-induced decline in capacity of 1.76m b/d in Iran and Venezuela from 2018-24 may appear appealing for other OPEC producers to make up that lost ground. However, the IEA projects a substantial increase in non-OPEC over the same period: an increase of around 6m b/d led by capacity additions in the US. OPEC’s room for manoeuvre, particularly over the next two years, will be limited should the producers’ bloc seek to avoid contributing to a market surplus. The call on OPEC in 2020 is estimated at just 30.13m b/d (and 30.4m b/d in 2021). That compares with January production levels of 30.83m b/d estimated by the IEA.

By the end of the 2018-24 period, however, the long-term (five-year) pace of growth in non-OPEC supply will have slowed from recent highs as the impact of the shale boom accrues into the base.

Source: IEA Oil Market Report 2019.

Source: IEA Oil Market Report 2019.