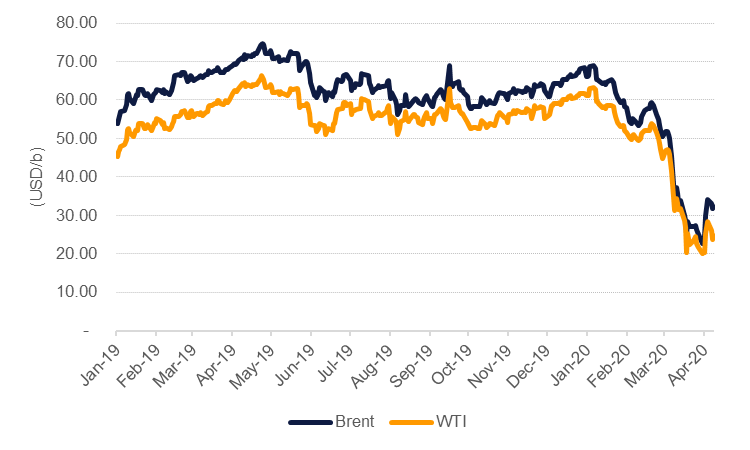

OPEC+ is due to hold a virtual meeting on April 9th to address the enormous imbalance in oil markets. Oil prices have oscillated in the last few days on waxing and waning expectations that OPEC+ will agree on production cuts in an effort to stabilize markets: Brent futures have risen more than 30% since April 1st, although they still remain below USD 35/b. The scale of cuts that would be required are cataclysmic. The IEA noted that even cuts of 10m b/d would still leave the market oversupplied by 15m b/d in Q2, causing inventories to explode, forward curves to widen substantially into contango and spot prices to remain highly volatile.

Source: Bloomberg, Emirates NBD Research

Source: Bloomberg, Emirates NBD Research

Leaving aside how much may actually need to be cut, we are assigning a low probability that a deal to cut production can be reached. At its last meeting OPEC+ failed to endorse even extending the production cuts that were in place for Q1 for the rest of the year. This time the level of cuts would be much more painful for producer economies to bear and there is no guarantee prices would move much higher than their current USD 25-35/b range given how weak demand is as a result of coronavirus-related shutdowns of major economies.

But our primary rationale for not expecting a significant breakthrough is that the positions of the main actors, notably Saudi Arabia and Russia, have not changed. Saudi Arabia remains unwilling to single-handedly balance markets by taking the heaviest burden of cuts and will only agree to cut output if others do so as well. The Kingdom has so far showed no sign of moving away from its higher production levels. The CEO of Aramco, Amin Nasser, said in March the company was “very comfortable” with prices around USD 30/b and that output would remain high—presumably around 12m b/d—into May. Aramco delayed announcing its OSPs until after this week’s meeting, giving it the flexibility to adjust prices higher or lower in response to the outcome.

For its part, Russia continues to insist that the US participates in any production cuts. Moreover, rhetoric between Russia and Saudi Arabia has degenerated over the last few days into who was responsible for the failure of the March meeting. Nevertheless, there have been some signs that Russia is tiring of the low prices: Russia’s energy minister, Alexander Novak, said the country had no plans to increase production from its roughly 11.3m b/d produced in March.

The barrier to a deal then remains how to get the US involved. Other producing countries that are dominated by a single state-linked producer have indicated they would be will to support production cuts: Norway and Brazil will participate in a G20 meeting after the OPEC+ summit to discuss their potential cooperation in cuts. But the US has no single national producer that could agree to cut output in a meaningful enough way to contribute to a 10-15m b/d agreement.

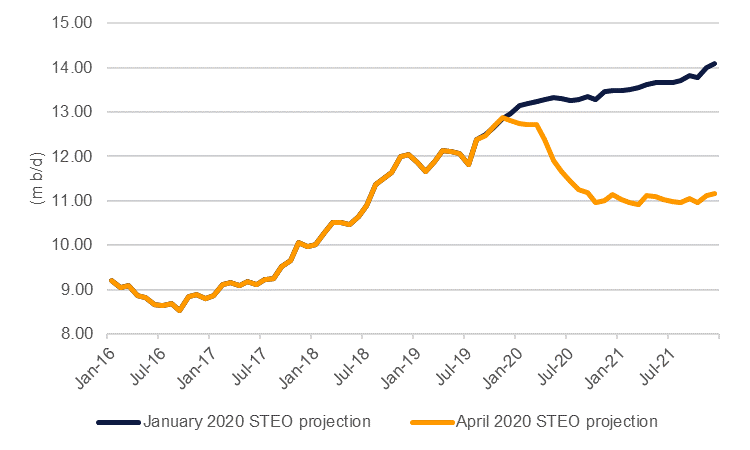

At a federal level, at least as far as President Donald Trump’s Twitter feed represents it, the US will not enforce cuts on producers, preferring the “free market” to sort out the imbalance. The collapse in oil prices will certainly lead to production cuts—data should start to reflect that over the coming weeks. The EIA has also revised its projections for oil supply growth in the US downward for 2020 and 2021. Producers in the US have slashed capital expenditure plans—with more than 120 rigs already out of service—to try and survive the rout in prices. Some producers even appear to be coming around to the idea of mandatory supply cuts in cooperation with OPEC+ producers to stabilize the market.

Source: EIA, Emirates NBD Research

Source: EIA, Emirates NBD Research

But there remains a fundamental imbalance between the structure of the oil industry in the US and that in producing countries like Russia, Saudi Arabia, or even smaller producers like Norway, that will frustrate efforts to balance markets through the heavy-handed tool of production cuts. Collectively, US production will fall this year, and the pace of decline may indeed be as severe as the EIA is projecting. But the thousands of oil companies that make up the oil industry in the US will not be able to directly participate in OPEC+ negotiations that would parcel out specific production target levels. The absence of a single voice representing US oil production has been a frustration for OPEC+ since 2015 when the producers’ bloc tried a market-share strategy. US production fell—as a market response to lower prices—but companies became more flexible and adjusted costs to allow for enormous growth once prices stabilized at higher levels. When OPEC reversed course and cut output from the start of 2017, US producers were able to take all of the market share ceded by OPEC and others.

The market conditions at the moment are not terribly different, aside from prices being much weaker. OPEC+ could agree to cuts but they would end up being self-defeating. Cuts would need to be deep enough to meaningfully address the oversupply in markets but not too deep to cause prices to rally to levels where more flexible producers in the US ramp up production again. As we noted in a previous report (“Should Texas join OPEC”, March 24 2020), the rocks behind the boom in US production haven’t gone bankrupt, only some of the companies that produce from them will. Letting the “free market” do the work of clearing excess production in the US (though bankruptcies of capex reductions for example) would mean the US oil industry comes out of the current price cycle leaner and able to operate at lower prices.

OPEC+ production cuts now would renew the cycle the oil market has endured since 2015. We are highly skeptical that the Trump administration—or any US administration—would voluntarily cap how much crude the US is allowed to produce. Achieving energy independence, or at least reducing reliance on imports of oil, is a relatively apolitical policy and the US government will allow companies the room to increase production if they find it profitable to do so. We are not suggesting that a cut agreement this week will mean that US output will spike in the following months. But when prices or financing conditions stabilize independent producers will seize the chance to raise output. Whether it happens this year or stretched out over the coming years, the dynamic remains the same.

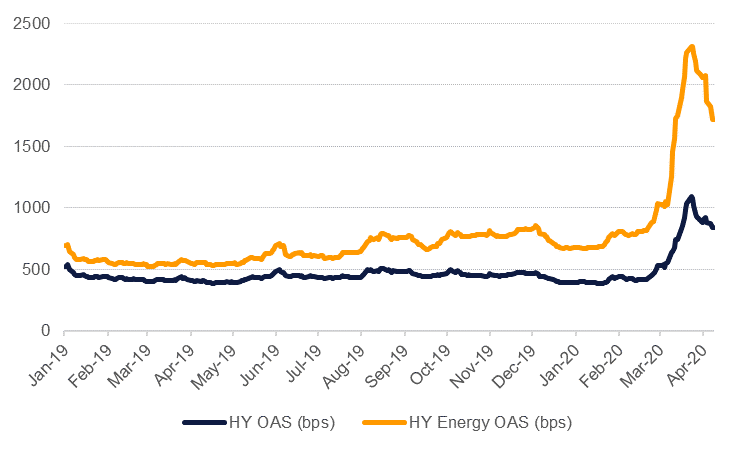

The US oil industry is certainly not invulnerable, however. Credit spreads on high yield energy companies have exploded and there has been a wholesale downgrade of the sector’s credit ratings in the last month. Results from Q1 will start to appear over the coming weeks and lower valuations for oil reserves will contribute to lower borrowing bases for leverage-dependent companies in upcoming financing negotiations. All the more reason for OPEC+ to keep the pressure on US producers via elevated production (and low prices).

Source: Bloomberg, Emirates NBD Research

Source: Bloomberg, Emirates NBD Research

The US oil industry is of a substantially different nature than the NOCs of OPEC+ producers, with different motivations and constraints. Treating it as though it is like any other oil-dependent economy is unlikely to work in the aim of restoring balance to markets. The impact of low oil prices will be straining all OPEC+ economies. But in order to avoid repeating the crash/boom cycle of 2015-19 a failure to come to agreement this week may actually be the best result if the objective is to put the US oil industry on its knees permanently.