The Covid-19 pandemic crisis has accelerated the transition to more remote patterns of working for many sectors, which poses fundamental questions regarding not only how we will work in future, but equally how we will live. While many will enjoy the lack of a morning commute, the ability to prepare one’s own lunch in one’s own kitchen, or potentially easier childcare arrangements, the benefits are not without their price. A lasting shift towards a working from home culture raises questions over widening inequality, the future of real estate in our towns and cities, and the funding of vital services and infrastructure. Failure by policymakers to look at these issues risks an ongoing flight out of city centres, and a subsequent loss in economic vibrancy.

The transition to working from home (wfh) is by no means guaranteed for all, and some firms will remain resolutely against it. Nevertheless, it seems certain that there will be a wider shift towards less time in the office for many white-collar workers even once the pandemic crisis is firmly in the rearview mirror and fears over crowded spaces and potential contagion have eased. While Goldman Sachs CEO David Solomon has called the present home working arrangement an ‘aberration’, maintaining that the bank’s culture demands a return to face-to-face operations and a personal touch, high profile firms such as BP, HSBC and Lloyds have all recently revealed plans for extending home working for many of their staff over the coming years. For those privileged enough to have been able to work away from the office through the pandemic crisis – those who have proved that they can maintain productivity levels, and who now have the required equipment and work spaces set up at home – the likelihood is that they will demand a certain measure of extended home working hereafter, even if just two days a week as BP has outlined.

.jpg) Source: Google mobility data for March 7, compared to baseline pre-pandemic levels, Emirates NBD Research

Source: Google mobility data for March 7, compared to baseline pre-pandemic levels, Emirates NBD Research

It is worth noting that it is higher-paid jobs that can usually be done from home and that lower-paid workers in the retail, nursing, hospitality, construction and manufacturing sectors are for the most part unable to benefit from this, just as has been the case over the past 12 months. As such, an extension of the wfh trend risks exacerbating already existing inequalities as it will be those on higher incomes who no longer have to spend money and time commuting and on all the other expenses associated with a day out working, while those already less well-off will see their expenditure unchanged. Inequality has an economic as well as a social cost, as more unequal societies see higher crime rates and lower life expectancies, and the potential for more volatile politics.

Source: Bloomberg, Emirates NBD Research

Source: Bloomberg, Emirates NBD Research

Nor will this be the only challenge to lower-income households posed by extended wfh; a shift away from city/town centre working puts all the ancillary services jobs that have built up to serve those working in busy office environments at risk. Even an average one-day per week at home for office workers presents the risk of a 20% drop in takings for cafes, burrito shops, dry cleaners etc, while outgoings such as rent or staffing costs remain broadly unchanged. Stores once ubiquitous in the streets of London have already put this train in motion, as formalwear store TM Lewin has moved its business entirely online. With the labour market in retail already under pressure from increased online shopping – another trend accelerated by the pandemic crisis – there is a potential for even more hollowing out of blue-collar jobs, on top of the challenge already posed by automation.

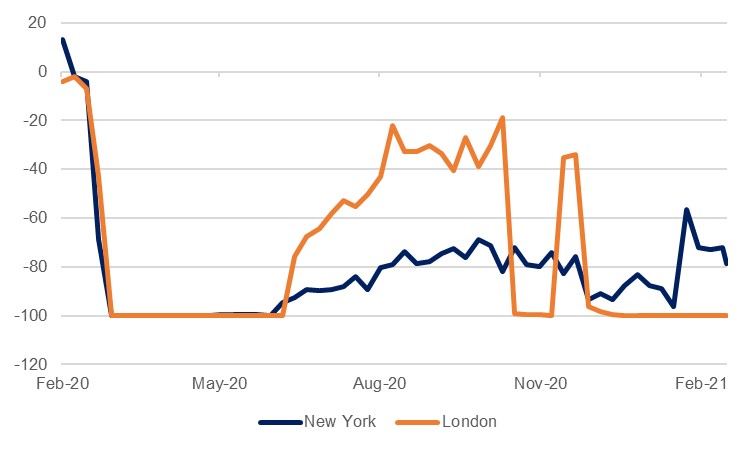

Aside from the employment issue, a move towards less time spent in town and city centres also raises questions regarding the real estate sector, as demand for office space falls and shops and restaurants close. Moody’s has projected that commercial real estate rents in the US will decline even more in 2021 than in 2020, and that they will not return to pre-pandemic levels until 2026. The ratings agency believes that San Francisco and New York will be among the worst affected, two major commercial hubs that have seen high-profile adoption of wfh, especially in the tech sector. In the UK, shops and restaurants have been forced to try and come to arrangements with their commercial landlords. Sandwich store Pret a Manger for instance has arranged turnover leases with many of its landlords, whereby rents are in part determined by a premises’ takings – but even this has not stopped the chain from shutting tens of its premises.

Even these concessions by landlords will not be sufficient to prevent closures, however, running the risk of increasingly bleak and hollowed-out commercial centres. The closure of high street stores was already a burgeoning trend prior to the pandemic, and will likely be vastly accelerated now with more cafes and restaurants also pulling down their shutters. This raises important questions for governments as to how to deal with this issue, with support in terms of lower business rates for instance unlikely to indefinitely paper over the cracks of a fundamental shift in lifestyles. The recalibration of office space into residential units could be a solution, making busy commercial centres places of habitation and leisure once more, but this would take concerted policy direction.

Source: Apartment List, Emirates NBD Research

Source: Apartment List, Emirates NBD Research

Away from commercial real estate, residential housing is also undergoing a shift due to increased wfh practices, as people look for greater space and place less of a premium on proximity to the office. Workers are far more prepared for an extra-long commute two or three days a week than they would be every day, meaning that buyers are increasingly looking further out from city and town centres for houses with spare rooms that can be used as offices, and some outdoor space. Rents in Greater London fell in 2020, but the outer-lying boroughs performed more strongly than those more central, a trend replicated in cities elsewhere in the UK and the US. In New York, the median rental for a two-bedroom apartment has fallen -20.8% y/y, compared to a national average of -0.8%. This is a trend we also expect to see more of in Dubai, where villa rental prices rose in January for the first time in five years (see Dubai Property: Transaction volumes recover for analysis of Q4 data).

There are definite arguments in favour of the wfh trend in terms of helping to distribute the benefits of the new economy more evenly around countries and in different towns, rather than in just a few choice commercial hubs. With higher earners potentially spread more evenly around a country rather than the usual brain drain exerted by the primary one or two cities, disparities between regions could dissipate. There is also an environmental argument in favour of the move, as the emissions associated with travel will be vastly reduced, while the number of disposable coffee cups and other related waste products from the average day at work will also fall.

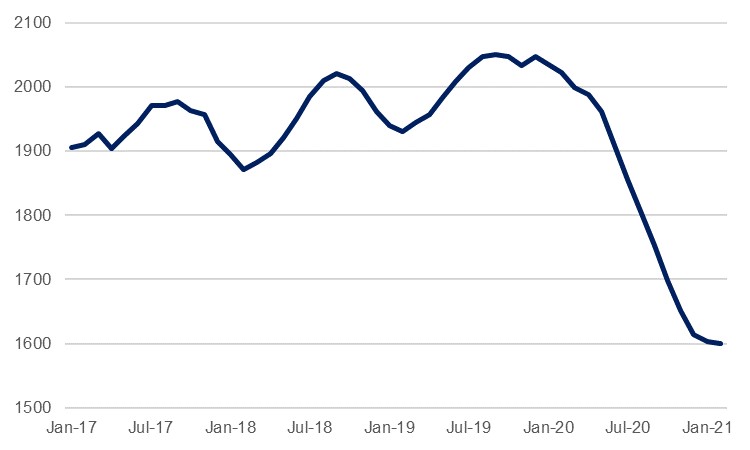

However, the transition to this will be a difficult one, as increased wfh will also pose key challenges for government and municipal budgets as tax revenues in town centres fall, making it harder to maintain essential services in major cities. With those wfh no longer using public transport meanwhile, transport firms will struggle to maintain their services and infrastructure with much-diminished revenues, and we have already seen increased government support for mass transport systems in major cities. In New York, the Metropolitan Transportation Authority has been reliant on the USD 8bn it received from the federal government and a further USD 3bn it amassed in short-term loans, but it will still have a sizeable hole in its budget over the next several years that will need plugging if it is to avoid cutting jobs and services. This raises the prospect of hikes to transport fates, as has already been seen in parts of the UK, raising the issue once again that wfh will increase inequality. The progressive solution, perhaps, is to introduce a wfh tax in order to ensure that the better off continue to share this burden and pay their share towards the upkeep of essential services even if their usage of these has reduced.

All of the above factors have given rise to increased discussion over the ‘death of the city’. While similar calls were made in other periods of technological advance – the advent of the telephone for instance – and subsequently proven wrong it does seem from our close-up perspective that the building blocks for a durable shift away from the dense living styles of cities are more accessible today than ever before. Many jobs can be done completely online, while the essential sharing of knowledge and skills that cities have hitherto provided is now made easier to carry out remotely via fully functional video-calling capabilities. At the same time, the pandemic crisis has made people question how closely they want to live and breathe with thousands of other people.

Nevertheless, it is likely far too early to start writing the city’s obituary, as has been proved time again in the past. While their popularity has ebbed and flowed – the flight to the suburbs in the second half of the twentieth century being a recent case in point – they have endured. As with David Solomon, many place a premium on the face-to-face interactions that office life provides and the potential for ideas generation that comes from this. For those starting out on their careers, time in the office provides essential opportunities to both learn from their seniors, but also to network and expand their social capital, something which is much more difficult to do remotely. Aside from being key in ideas generation in business, cities are also the primary birthplace of artistic movements, and this will remain a key draw. Many workers will prefer a hybrid system with one or two days at home like that proposed by BP and the rest in the office – not least because this makes them less vulnerable to salary cuts or the potential outsourcing of their jobs to cheaper labour markets abroad. Facebook has already announced plans to adjust salaries for remote workers dependent on their location.

All the same, while a complete move to wfh is unlikely, a fundamental shift is already underway, and policymakers will have to think hard about what form they want the city to take, and how to support those businesses and workers negatively affected by the changes.