The aluminium market has so far shrugged in response to the US Commerce Department recommendations that tariffs be imposed on metal imported to the US. The Commerce Department’s plan now has to be either endorsed by US president Donald Trump or he can scrap the plan in favour of something different entirely. Given the president’s protectionist stance on international trade—he has proposed scrapping NAFTA and put in place tariffs on imports of washing machines—we would expect some form of protectionism related to metals markets to be put in place by the US but likely with a limited impact on markets in the near term.

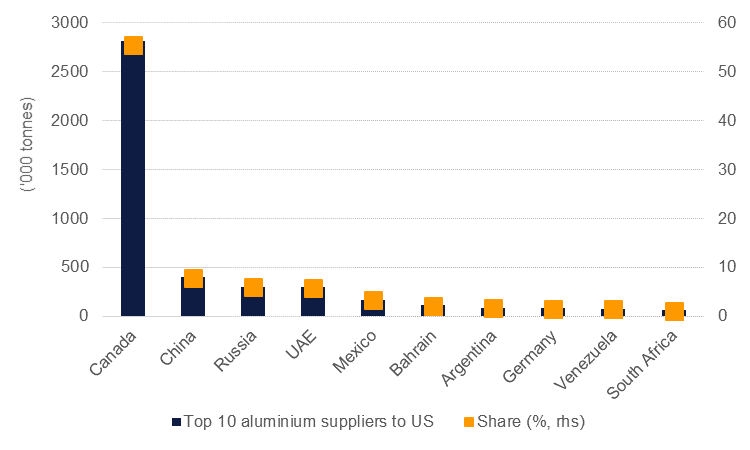

The proposed tariffs ostensibly target China, the world’s largest producer of aluminium, which the Commerce Department links to the decline in US output. China is only a relatively small exporter of metal to the US, taking a far distant second place to Canada which has not been specifically named under new tariffs but may be limited to keeping exports at 2017 levels. US aluminium production has been in long-term decline as it has lost competitiveness to alternative producers elsewhere in the world benefitting from lower costs and, critically, easier access to power. As far as the domestic market goes, the proposed tariffs would most likely end up hurting metal consumers via higher prices in the US—in particular hitting automotive and packaging industries—more than they would support domestic smelters.

China’s aluminium industry is currently grappling with its own domestic turbulence as the government cracks down on illegal capacity and enforces pollution-related shutdowns over the winter months. Production has soared since 2010 as output has moved westward in the country, allowing smelters to integrate with captive power plants and avoiding having to compete with other users for grid power, an issue that has led to smelter shutdowns in the US and Australia in particular. Chinese exports of aluminium have followed production higher, rising 4.6% last year at 4.8m tonnes, but as noted, few of these are finding their way to the US. Exports may push even higher this year as inventories in China have been moving higher, sending a sign of somewhat underwhelming domestic demand in the face of enormous domestic production and a declining domestic premium over LME prices encourages trade.

If president Trump follows through with imposing protectionist tariffs on metal we would expect to see some form of retaliation against imports of US goods abroad. Already the EU has threatened agriculture products with a retaliatory tariff and we would expect China could follow suit on products such as soybeans or corn.