The global economy underwent a period of marked integration after the end of World War II, with goods, services, technology, money, and people increasingly moving across national borders. These flows ratcheted up even further in the 1990s with the increasing integration of economies like China and Russia into the global market, and the expansion of the European single market. Critically it wasn’t just the volume of trade and capital flows that rose over this period but also the complexity of linkages across borders.

Since the global financial crisis (GFC) of 2008, companies, individuals and politicians have called into question the value of globalisation, and governments across the world have stepped up protectionist measures in an attempt to support local industries.

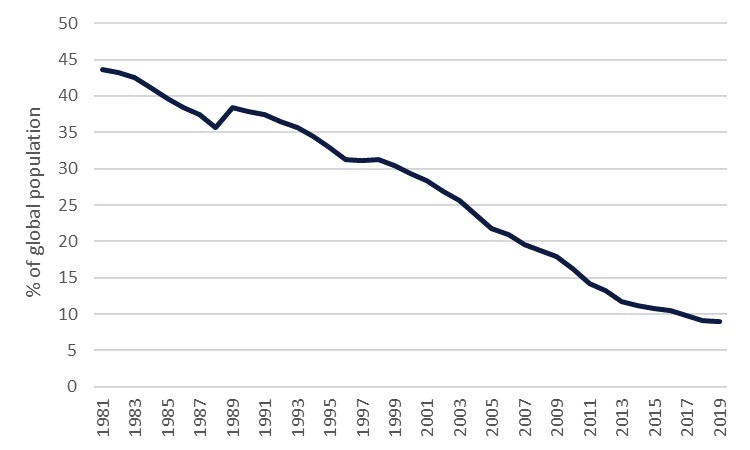

The World Trade Organization (WTO) credit globalisation with being a major contributor to the substantial reduction in global poverty seen since the 1990s. In large part this was achieved by governments easing restrictions on trade and investment, which in turn reduced costs and increased efficiency by allowing companies to source different parts of their supply chains from a variety of suppliers. Businesses could therefore seek out the least expensive source markets for both intermediate goods and labour, leading to a rise in offshoring, with shifts in production to poorer nations. This proved to be a boon for developing nations which benefited from rising FDI and the transfer of technology from developed economies.

The benefits of globalisation aren’t however limited to developing economies, with advanced economies benefitting from cheaper goods and services when they are produced in less expensive countries. More broadly, there are also global gains that might be derived from closer international cooperation, with action on key issues such as climate change potentially more likely in a more integrated world economy.

Source: World Bank

Source: World BankDespite evidence of globalisation’s net benefit to the world economy, critics point to several drawbacks, chief amongst which is the distributional impact within advanced economies. More expensive low-skilled workers in advanced economies, such as the USA, lose out to households in developing nations with the off-shoring of production facilities. This exacerbates income inequality within advanced economies, as businesses benefit from lower costs and expanding export markets, at the expense of low-skilled domestic workers.

Critics also point to how rising global integration can increase risk and fuel crises when exogenous shocks hit the global economy. For example, high levels of capital mobility and interconnected financial systems are often cited as a contributing factor to the 2008 global financial crisis. More recently, observed fragilities in supply chains seen both during the Covid-19 pandemic and at the start of the Russia-Ukraine conflict have contributed to bottlenecks and rising prices.

Along with increasing negative sentiment toward globalisation, there has also been a growing narrative that the global economy is in a phase of de-globalisation. There appear to be some tentative signs of a slowdown in the pace of integration, although – consistent with the view of the World Trade Organization – claims of wholesale de-globalisation appear “greatly exaggerated”.

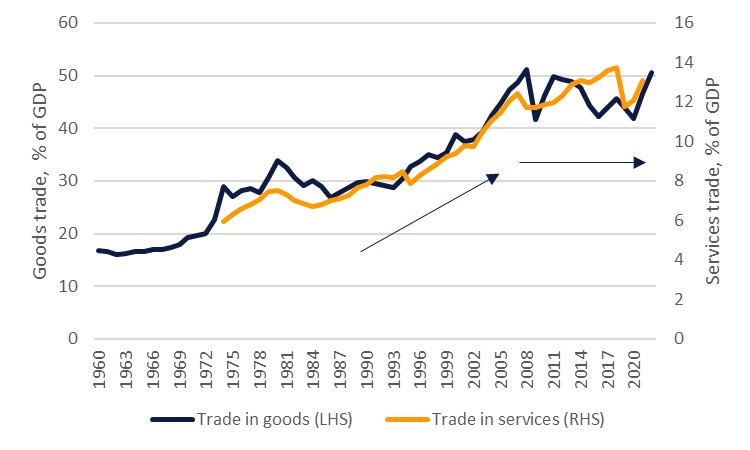

Source: World Bank

Source: World Bank

One of the metrics used to measure globalisation, the share of goods trade in global GDP, appears to have plateaued from roughly 2008 onwards, after rising at a rapid pace from the 1970s. Other measures, including the underlying trend in global FDI and global value chains’ share in global trade, follow a similar pattern of strong growth up to the late 2000s, followed by a slowdown in the pace of change.

What has driven this slowdown?

The observed slowdown is due partly to the shift in preferences away from goods towards services, which are inherently harder to trade. But several other factors have also likely played a role in the gradual slowing in the pace of globalisation. The first is the global financial crisis of 2008, which created uncertainty and stoked fears of financial sector contagion when capital is allowed to flow freely.

A variety of geopolitical events have also played a role. Chief amongst these is America’s trade war with China, which started at the beginning of 2018, with the Trump administration applying tariffs on Chinese goods in a bid to force China to address allegations of intellectual property theft. More generally recent years have seen a sharp rise in the number of trade restrictions being imposed globally. A second Trump term may well add impetus to this trend, with reports suggesting that he plans to apply a 10% tariff on all imported goods if re-elected as president.

Looking ahead, concerns about the negative aspects of globalisation, including recent supply chain fragility, is likely to drive two primary changes in the way the global economy operates.

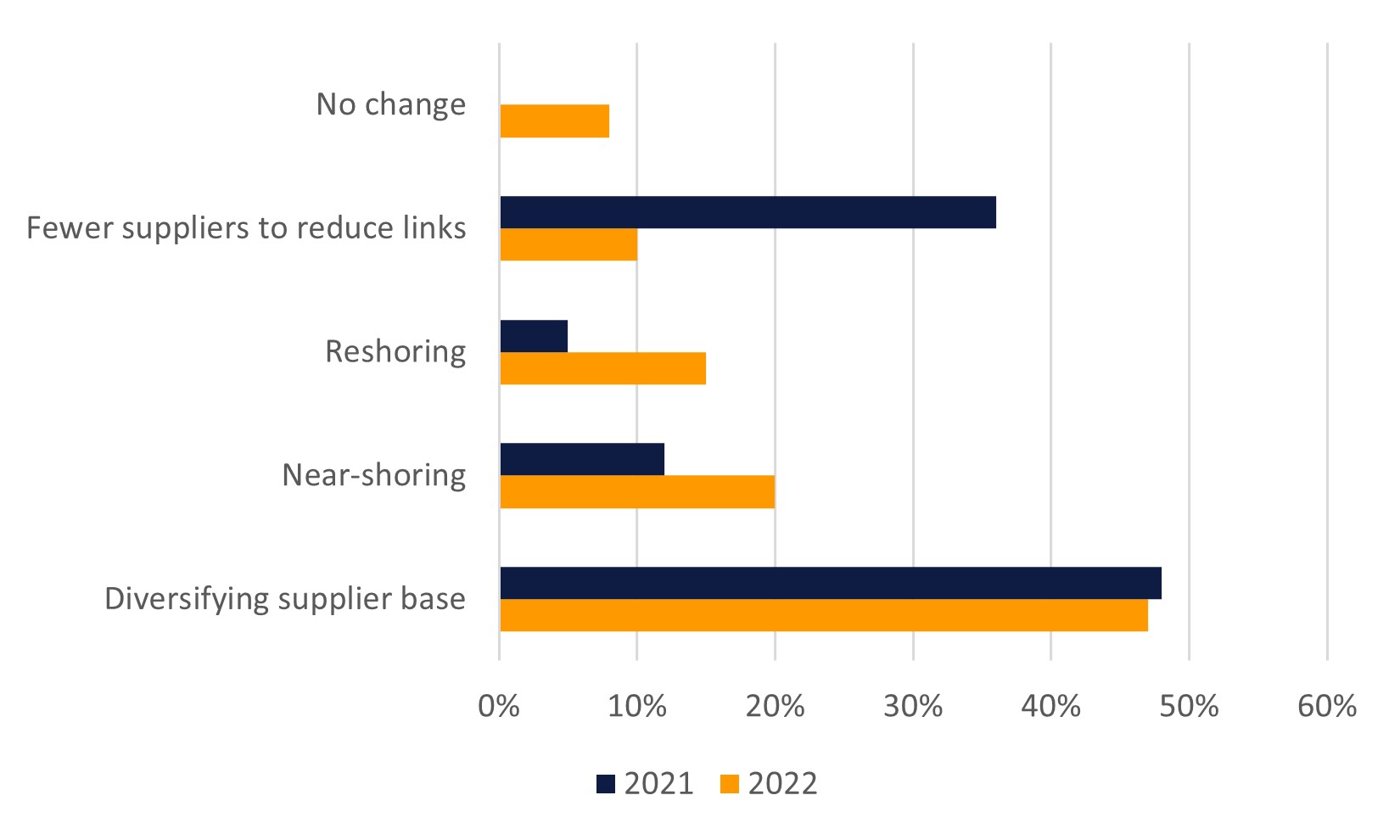

The first is that companies are likely to move away from very lean supply chains. While efficient, these “just-in-time” supply chains are not resilient and are subject to disruption when global shocks do occur. There is some evidence to suggest that companies have started making changes, with almost half of respondents to the Economist Impact Trade in Transition global survey reporting in both 2021 and 2022 that they had diversified their supplier bases.

A new paper from the Bank for International Settlements, however, suggests that the current shift to diversification of supply chains may do little to make them more resilient. This is especially true of links between Chinese producers and American buyers, with supply chains in fact becoming longer and more complex. While the share of US firms in China’s customers has fallen by 10ppt since the end of 2021, it appears that Asian firms are now acting as distributors, buying from Chinese suppliers, and reselling to US firms, with businesses often unaware of the real origin of goods.

A more meaningful form of diversification could include “vertical integration”, where companies buy up suppliers, such as Tesla breaking ground on a lithium refining factory to ensure supply for battery production. Another option is for companies to stockpile essential inputs, with respondents to the Trade in Transition survey reporting that they held 10.1 weeks of inventories in 2022, up from 8.9 weeks in 2021.

Source: Trade in Transition survey

Source: Trade in Transition survey

The second is a move towards regionalization, under which production facilities are moved back to domestic markets (reshoring), geographically close neighbours (near-shoring) or political and economic allies (friend-shoring).

While evidence points to an increasing share of companies pursuing this option, it still isn’t the dominant strategy amongst corporates. In 2022, 20% of companies in the Trade in Transition survey reported that their approach to strengthening supply chains was to near-shore activity, up from 12% in 2021. Another 15% said they were reshoring activity, up from 5% in 2021. The current dominance of diversification as a strategy may be due to the material costs likely to be associated with reshoring, near-shoring and friend-shoring, as many MNEs don’t actually own the production process, but rather use a network of suppliers producing on their behalf.

While complete self-reliance is not only impractical but also impossible for almost all countries, there may be more material shifts in some strategic industries. These industries may see the relocation of production facilities happening more quickly, driven by government policy decisions, with subsidies and tax incentives used as a mechanism to encourage private firms to relocate production.

A prime example of this is the semi-conductor industry, with several major economies providing support. The US “CHIPS and Science Act”, the European “CHIPS” act and the “Made in China 2025” strategy are clear examples of government intervention to change the behaviour of the private sector to increase the individual country’s share of the global semi-conductor market. The US has in addition placed wide-ranging export restrictions on some advanced chips, since September 2022, preventing their export to China.

The bulk of academic literature points towards an unambiguously negative effect on the global economy as a result of a reversal in globalisation – generally modelled as a breakup of the global economy into regional blocs. These studies tend to highlight the negative impact on developing countries due to declining trade and reductions in FDI related technology transfers. But it is also worth noting that advanced economies also suffer due to a general decline in global growth.

In addition, there are other potential channels which may also affect the world economy. Increased fragmentation may mean that when a global crisis does occur, international coordination is less likely. Examples of this could include less coordination between central banks, reducing the number of swap lines available to manage liquidity crises, or that global bodies such as the IMF and the World Health Organization receive less funding. One consequence of this is that governments might elect to building their savings buffers as a way of self-insuring against shocks, which in turn could hamper domestic growth.

Finally, while less financial integration across capital markets may mean that contagion across regions is less likely to occur, when a crisis does hit a country or region, it may be deeper because there is less diversification.

Is there evidence of a change within the UAE?

GCC nations predominately appear in global value chains as exporters of raw materials and importers of intermediate and finished goods. The UAE is, however, seeking to change this, by promoting their domestic manufacturing sector. The government announced Operation 300bn, the 10-year strategy to expand the contribution of the industrial sector from AED 133bn in year 2018 to AED 300bn by 2031. The strategy seeks to prioritise the development of 10 sub-industries, including food and beverage (F&B), machinery and equipment and pharmaceuticals.

This policy to support manufacturing is part of a broader push towards building resilience in the economy. The development of nascent high-tech industries that have not previously featured heavily in the country’s manufacturing base will help to diversify exports and support technology and skills transfer into the UAE.

An additional benefit from the diversification of the economy into more high-tech manufacturing may be that over the longer-term the UAE could be well placed to take up higher value-added roles in GVCs should friend-shoring strategies become more entrenched in advanced economies.

Moreover, the strategy being adopted by the UAE government appears to strongly favour a system in which barriers to trade are reduced, rather than hiked. This is evidenced by the continued negotiation of a significant number of Comprehensive Economic Partnerships agreements (CEPA).

These CEPAs are more than just trade agreements and can cover investments and the movement of labour, deepening overall economic integration with partner countries. The CEPAs should lower tariffs and boost investment and technological transfer, as well as diversify sources of imports and build deeper relationships with a wider range of trade partners. Consistent with the benefits of increased integration, the IMF estimates this could raise productivity and GDP growth by up to 2% over the medium term.