North African economies are particularly exposed to the upwards drive in global food prices precipitated by the conflict in Eastern Europe, which will further exacerbate the already extant effects of regional droughts on food supply. Food inflation in the region was ticking higher even before the latest price shock fed through, and the pressure this will put on households will lead to difficult policy decisions for regional governments and central banks, especially as it comes in tandem with the related move higher in oil prices. Higher inflation, depreciating currencies, wider current and fiscal deficits and tighter monetary policy will all weigh on the growth outlook this year, even in the increasingly unlikely event of a speedy resolution to the Ukraine conflict.

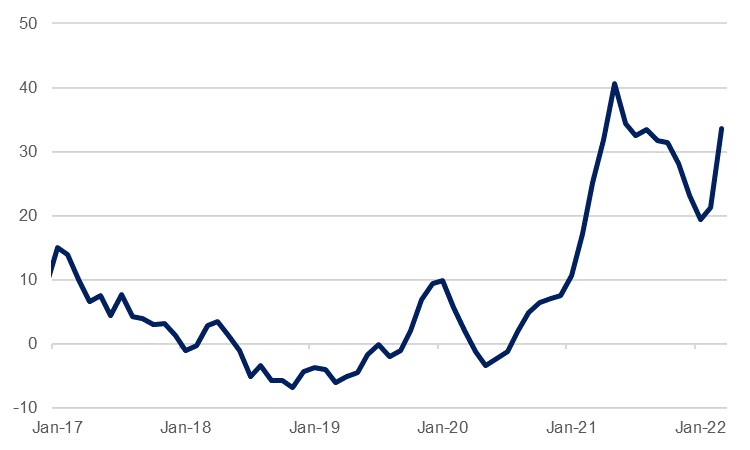

Accounting for around a quarter of global wheat exports, alongside significant volumes of other grains and animal feeds, Ukraine and Russia are hugely important for global food markets, and the disruption caused by Russia’s invasion of its neighbour in February has driven prices sharply higher; while benchmark wheat futures have come back from the initial spike, they remain around a third higher than they were prior to the conflict. Global food price inflation had already been at levels last seen a decade ago over the past 12 months as supply chain disruptions caused by the Covid-19 pandemic persisted and now the deceleration that had been in play since May last year has reversed sharply: global food inflation came in at 33.6% y/y in March according to FAO data as prices jumped 12.7% in a month.

Source: FAO, Bloomberg, Emirates NBD Research

Source: FAO, Bloomberg, Emirates NBD Research

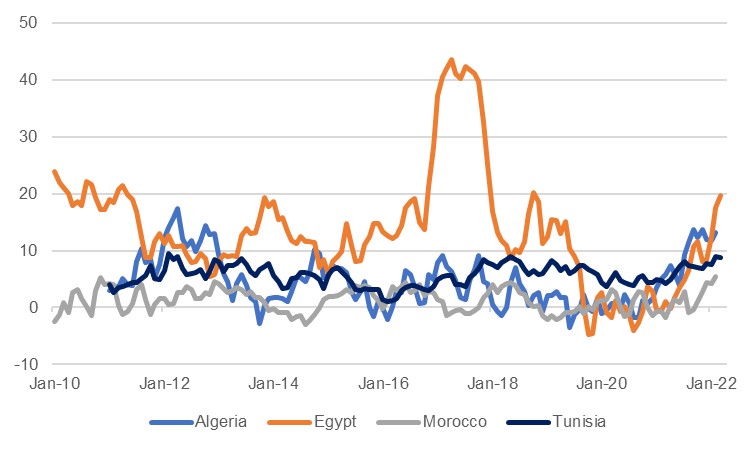

Aside from the general global price surge that is affecting countries all over the world, the five North African countries are particularly reliant on wheat imports from the Black Sea region, and higher food prices will likely push inflation higher from the already elevated pace of price growth. In March, 19.7% y/y food price inflation in Egypt contributed to a headline figure of 10.5%. In Morocco, where the situation is exacerbated by a drought which will see a poor harvest this year (see Morocco: Growth downgraded on drought pressures), food price inflation was already 5.5% in February, while Tunisia and Algeria saw food inflation of 13.2% and 8.7% respectively that month. Ukraine and Russia account for some 80% of wheat imports in Egypt and they are also the biggest suppliers to Libya and Tunisia. Algeria and Morocco are less exposed, but even in Morocco, Russia and Ukraine accounted for 22% of wheat imports in 2020. As is usual in developing countries, food accounts for an outsize share of the CPI basket, so any acceleration in food inflation will drive the headline reading higher also.

Source: Haver Analytics, Emirates NBD Research

Source: Haver Analytics, Emirates NBD Research

Conscious of the socio-economic dangers of rising bread costs, the authorities are making efforts to try and contain the fallout of these price pressures on the population at large. In Egypt, the government has fixed the price of unsubsidised, free market bread for three months, with stiff fines for anyone caught trying to price gouge. Any previous discussion of rolling back on bread subsidies has also been put aside, pensions and public salaries have been raised, and wheat exports have been banned for three months as well. Even prior to the Ukraine crisis, the Moroccan government had already earmarked upping its spending on wheat subsidies by 15% this year as it looked to offset the effects of the drought there and this will likely have to be raised once again. The problem for the region’s governments is that their ability to distribute largesse is limited by the economic strife wrought by the Covid-19 pandemic over the past two years.

Source: Haver Analytics, Emirates NBD Research

Source: Haver Analytics, Emirates NBD Research

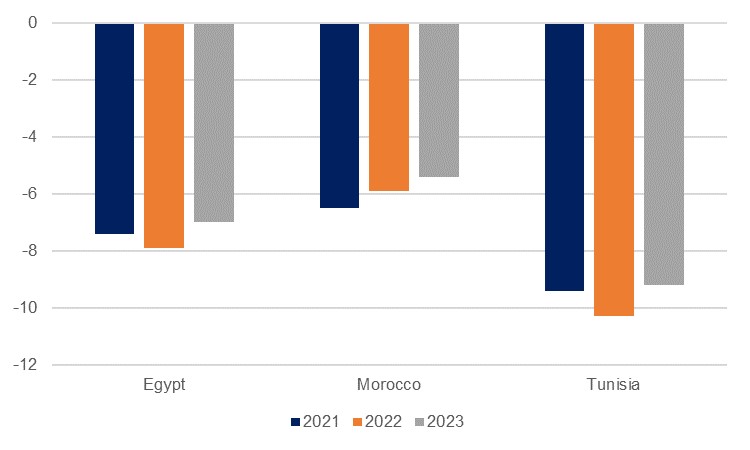

North African governments were already coping with increased debt loads and having to raise subsidies again this year will push back any planned fiscal consolidation – especially for those countries that will not enjoy a hydrocarbon export windfall – and we have adjusted our budget deficit forecasts accordingly. In Egypt we now predict a budget deficit equivalent to 7.9% of GDP in the year ending in June, compared with -7.4% in the previous fiscal year, and we see only a gradual narrowing in fiscal 2022/23. Likewise in Morocco and Tunisia we now see a much slower reduction of the deficit this year than we had previously anticipated. Tunisia’s ministry of finance had sought to reduce the public sector wage bill and subsidy expenditure this year – and fuel prices were hiked for the third time in 2022 this month – but the pace of this will likely be much slower than initially hoped, especially given the strength of the local UGTT labour union and the highly fractious political environment at present.

Current accounts are also coming under pressure, with higher food prices one more issue to deal with on top of the higher energy costs, global monetary tightening and the impact of the Russia/Ukraine war on visitor numbers and spending – the two countries are key source markets for North African tourism sectors. The Moroccan central bank expects import expenditure to rise by 14.9% this year, outpacing the expected rise in exports, while in Tunisia the latest communiqué from the BCT noted that the current deficit had already widened in the first two months of the year compared to the corresponding period in 2021, and reiterated ‘its call for an utmost vigilance with respect to the impact of Russian-Ukrainian crisis on global macro-economic balances.’ Both countries held rates steady at their March MPC meetings, but we expect that the rest of the year will see a number of rate hikes, just as we expect further moves higher in Egypt. The CBE surprised with an early hike in March, raising rates by 100bps several days before its scheduled meeting, and we expect a further 300bps over its next two meetings as the bank looks to reestablish the real interest rate differential that has made the country attractive to international investors over the past several years.

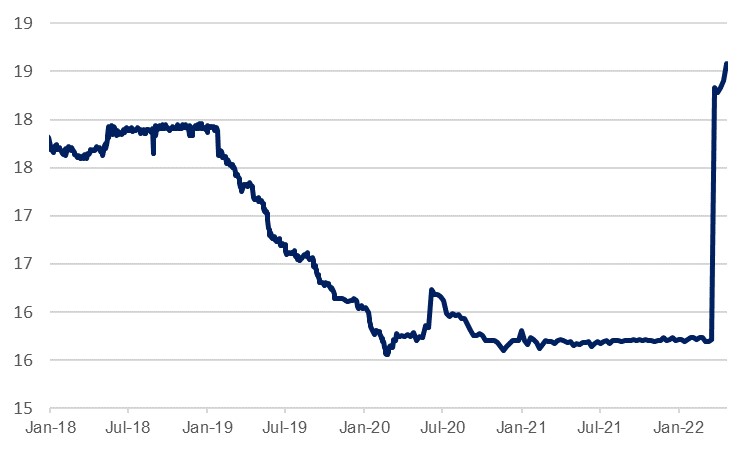

Egypt’s March rate hike happened at the same time as a significant 16% depreciation by the pound after a prolonged period of stability, further underlining the strains the current situation is exerting on regional economies. The more flexible exchange rate and the meaningful rate hike were likely a prerequisite for a renewed support programme with the IMF, and the Fund issued a statement in late March that the Egyptian authorities have sought their assistance once again. Having in the interim received substantial funds from the GCC – Saudi Arabia has deposited a further USD 5bn with the CBE, and has also pledged billions of dollars of investment, as have Qatar and the UAE’s ADQ – and adhered to a flexible currency, the likelihood is that this will be forthcoming. It is worth noting here also that the cheaper pound will also induce inflationary pressures.

Source: Bloomberg, Emirates NBD Research

Source: Bloomberg, Emirates NBD Research

By contrast, Tunisia is severely lacking the unity of purpose that will be required to take the difficult decisions that will pave the way to a new IMF deal any time soon, meaning that the country’s economic stresses will continue. Ratings agencies Fitch and Moody’s have downgraded Tunisian debt to junk status, and while the central bank has made calls to reassure investors that a debt restructuring is not on the cards, political paralysis and a failure to implement necessary reforms will stymie any new IMF deal for now. A statement from the IMF in March noted ‘further progress in the technical discussions with the Tunisian authorities’, but the UGTT has since declared that it is ready to implement a general strike in order to reject proposed economic reforms.