Lebanese political parties agreed upon a new prime minister-designate yesterday, nominating Mustapha Adib, the former ambassador to Germany, to the post. Lebanon has had a caretaker government since the resignation of Hassan Diab and his cabinet in the wake of the Beirut explosion on August 4. Adib must now try to form a government, a process which has been a drawn-out affair in Lebanon in recent years, but which he yesterday cautioned must be done in record time if the country is to implement its urgent reforms, unlock the USD 11bn in CEDRE funding pledged in 2018, and secure a crucial IMF deal. Adib faces an uphill task in righting the Lebanese economy given the myriad of crises in the country in 2020, just one of which alone could have been sufficient to push the economy into a recession. Barring an unexpected rapid resolution in terms of securing an IMF deal, we project that the contraction will run as deep as -30.0% this year.

Source: UN, Emirates NBD Research

Source: UN, Emirates NBD Research

Questions regarding Lebanon’s economic stability had been rising for several years. The failure by successive governments to reduce the fiscal deficit and bring down debt levels (among the highest in the world), or to implement the reforms required by the Paris Club of lenders to unlock the USD 11bn of funding pledged in 2018 steadily eroded confidence and raised fears regarding debt defaults and the pound’s peg to the dollar. This was especially the case as regional financial support appeared to be less forthcoming than it had been in the past. These simmering issues started to come to the boil in October 2019, as demonstrations initially protesting the imposition of a tax on VOIP provider WhatsApp started to voice wider discontent, ultimately resulting in the resignation of Saad Hariri’s government. The subsequent political uncertainty began to further shake confidence in the country which had long relied on foreign inflows into its banking sector to maintain its financial system, with the end result being Lebanon’s first default on its foreign debt on March 9 when it failed to repay a USD 1.2bn Eurobond.

Since then, Lebanon’s problems have only grown, with the financial, economic and political crises compounded first by the coronavirus health crisis which has pushed most economies around the world into recession, and then by the enormous explosion in Beirut on August 4, which destroyed a large part of the city around the port. The damage wrought by the blast reportedly killed 190 people, injured a further 6,000, left over 300,000 homeless, and could ultimately cost USD 15bn.

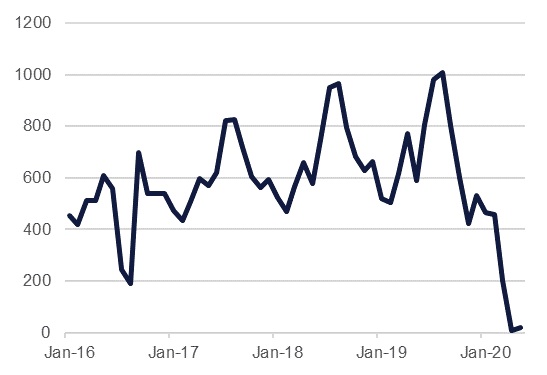

Even prior to the explosion, the economic impact of Lebanon’s problems was becoming clear in the data, with high-frequency data points underscoring just how parlous the situation had become. The country’s PMI survey, which was already perennially in contractionary sub-50 territory, fell to just 30.9 in April, indicating a sizeable shrinking in the private sector. The global lockdown which grounded flights all around the world, alongside the local closures in Lebanon itself, saw visitor arrivals to Lebanon fall to just 7,721 in April, compared with 770,258 in April the previous year. Hotel occupancy has plummeted as a result, and this will exert a heavy toll on the tourism sector, which accounts for some 18% of GDP according to the World Travel & Tourism Council, and is an important source of FX and employment (19.2%). Container throughput at the Port of Beirut declined 33% y/y in H1, while new cars registered over the period declined by 71%.

Source: Haver Analytics, Emirates NBD Research

Source: Haver Analytics, Emirates NBD Research

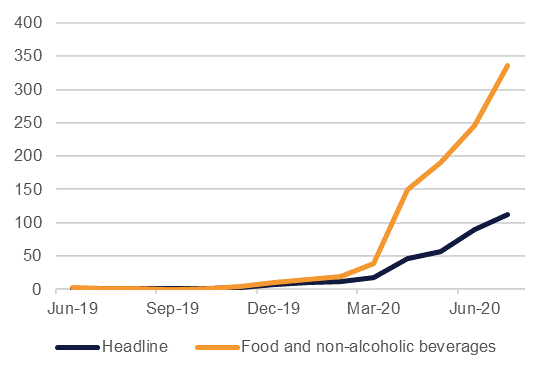

Alongside this fall in activity indicators has been the collapse of the Lebanese pound on the parallel market, and the massive spike in inflation which will have severely curtailed household spending power. The pound has lost around 80% of its value to trade at around LBP 7,500/USD (compared with the official rate of LBP 1,507.5/USD), and this brought y/y inflation to 112.4% in June, compared with 89.7% in July.

Most concerning for social stability is the rise in food prices, which increased by 336.2%, up from 246.6% the previous month. The more-than-threefold rise in food prices will likely have been compounded further by the Beirut blast, and inflation will likely push higher over the next several months. According to a Reuters report, the central bank can only afford to subsidise essential imports at the official exchange rate for three more months, which would see prices rise even quicker if a new deal with the IMF or international creditors is not reached. Aside from the erosion of spending power through inflation, the loss of homes and livelihoods caused by the explosion will also dampen private consumption, which usually accounts for over 90% of Lebanon’s GDP. In such a scenario the economic contraction in Lebanon this year is likely to be severe, even as it is offset by a collapse in imports.

Source: Bloomberg, Emirates NBD Research

Source: Bloomberg, Emirates NBD Research

The damage wrought by the explosion has made the need for Lebanon’s key players to come to agreement on the reform process, and to secure an IMF deal, even more pressing. The country announced it was formally seeking the Fund’s support in May (see Lebanon seeking IMF support), but since then discussions have floundered as disputes over the size of the hit to be endured by the banking sector came to the fore. Adib has been urged by French President Emmanuel Macron and the IMF to come forward with an agreed proposal as soon as possible, but the horse-trading that usually proceeds the formation of a new government in Lebanon could hold this process up. What seems increasingly likely is that any deal with the IMF will necessitate a recognition that the official exchange rate is no longer tenable, with a devaluation towards the parallel market rate probable.