News out of Lebanon over the past week has been positive for the country’s recovery prospects from its current crises. The formation of a new government and the vocal commitment by new Prime Minister Najib Mikati and President Michel Aoun to resuming constructive talks with the IMF and other bodies could pave the way for a new reform programme and much-needed financial support. However, even if the government manages to start implementing the long-called for economic and financial reforms and pledged money begins to flow in, Lebanon has suffered multiple shocks over the past 18 months or so. Once the contraction is halted it will take substantial time and effort to rebuild the economy, which will remain far smaller than it was in 2019 for some years to come.

.jpg) Source: UN, Emirates NBD Research

Source: UN, Emirates NBD Research

Following an estimated -27.1% real GDP contraction in 2020, we project a further -4.7% in 2021, with the risks to this outlook weighing heavily to the downside. As of September, there has been no material improvement in any of the factors that weighed on the economy in 2020, and while the one-off shock of the August Beirut port explosion has not been repeated, the Covid-19 crisis, the collapse of the currency and the resultant elevated inflation has continued unabated. By the official exchange rate of LBP 1,507.5/USD, the Lebanese economy will be -19.1% smaller in nominal terms at the end of 2021 than it was at the end of 2019, according to our forecasts. However, the official rate is used for an increasingly small number of imports. By the current parallel exchange rate, which is at LBP 16,350/USD at the time of writing on September 15, the Lebanese economy will be just USD 4.0bn this year, down from USD 53.4bn in 2019.

.jpg) Source: Haver Analytics, Emirates NBD Research

Source: Haver Analytics, Emirates NBD Research

The central bank had been using its reserves to prop up fuel imports at a subsidised rate of LBP 3,900/USD, but in August, former governor Riad Salameh announced that it could no longer afford to do so as its FX stockpiles dwindled. Even government plans to temporarily subsidise around half of the difference at LBP 8,000 would still exert considerable price pressures, fueling inflation which has already averaged 133.8% y/y over January to June, following an average 84.3% in 2020. Salameh said that reserves had fallen to USD 14bn in August, down from some USD 38bn at the start of 2020, just prior to Lebanon’s debt default. A disbursement of USD 1.1bn in SDR by the IMF this week, part of its global allocation of SDRs to countries affected by the coronavirus crisis, will help fund some urgent needs, but substantially more is required.

.jpg) Source: Bloomberg, Emirates NBD Research

Source: Bloomberg, Emirates NBD Research

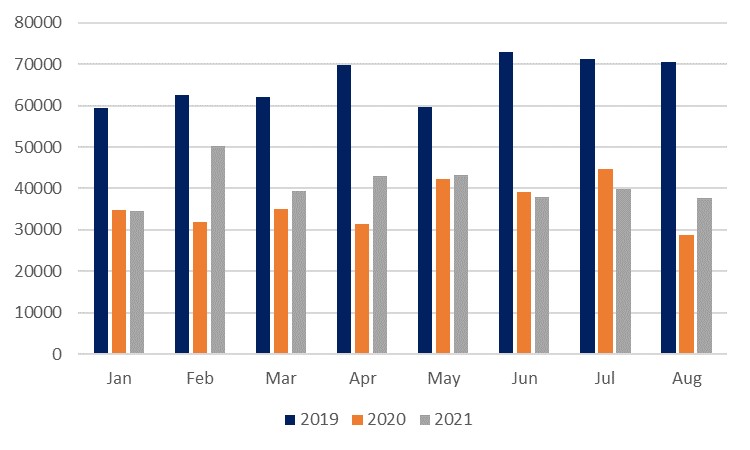

The financial collapse has weighed on every facet of the Lebanese economy. The high inflation rate, alongside rising unemployment levels and measures taken to tackle Covid-19, will have substantially constrained private consumption levels. A recent UN report said that 78% of Lebanese were now living in poverty. Local (ie not including transhipment or re-exports) container throughput at the Port of Beirut over January to August this year was down -38.4% compared with the corresponding period in 2019. Meanwhile, fuel shortages have exacerbated Lebanon’s long-standing issues around power generation, further hindering a private sector which is also struggling with new challenges around financing and credit. Electricity production in Q1 was down -9.2% y/y and will have contracted further still through the summer. The PMI survey has stayed resolutely contractionary over the past several years even prior to March last year and came in at 46.6 at the latest (August) reading, while the coincident indicator has fallen back to levels last seen at the close of 2001.

Source: Port of Beirut, Emirates NBD Research

Source: Port of Beirut, Emirates NBD Research

The IMF lists a number of recommendations for Lebanon, progress upon which would likely be a prerequisite for any substantial support beyond the sort of urgent funding needs that it has recently provided. These include improving ‘weak governance’ and ‘strengthening the anti-corruption framework’, alongside ‘restructuring the financial sector’ and ‘implementing a fiscal strategy.’ These are similar requirements to those required for the release of the CEDRE funding pledged in 2018 and have proved challenging for previous governments to meet given structural issues and vested interests at play.

All of this is not to undermine the positive news out of Lebanon over the past week but only to underscore the breadth of the challenge the new government has ahead of it. The economic collapse has driven a new brain drain as Lebanese have been forced to seek opportunities abroad, and this will make it even harder to reinvigorate the economy down the line. Nevertheless, it is undoubtedly a positive step forward. Mikati has stated that he is keen to reengage with the IMF after talks around a bailout collapsed last year, and perhaps his government of technocrats will have more success in implementing the called-for reforms upon which any funding will be predicated.