Fiscal deficits and public debt loads have expanded significantly through the Covid-19 crisis but with a growing light at the end of the tunnel the conversation is turning towards a post-pandemic future, and politicians are increasingly acknowledging the widening hole in their finances. Governments are not taking away the support just yet – indeed, in some cases they are still expanding it – but they are making noises about fiscal responsibility and bringing down public debt levels in the future. All the same, there are two sides to the debt/GDP equation, and while shrinking the numerator is one way to bring the ratio down, policymakers will need to balance the need to grow the economy – the denominator – at the same time. With interest rates at record lows the likelihood is that governments will take advantage of the cheap money for now and will not be taking away the punch bowl just yet.

Over the past 12 months, developed markets have unleased spectacular amounts of fiscal support and stimulus as they have sought to keep the Covid-19 healthcare crisis from developing into a long-lasting economic and financial crisis. To varying degrees, governments have introduced furlough or kurzarbeit schemes, added special pandemic-related unemployment benefits, or implemented direct payments to qualifying individuals in a bid to keep households solvent and help maintain some level of consumption. Businesses have also received direct support, while tax cuts and waivers have further aided the economy. At the same time, government revenues have diminished as economies underwent the severest contraction in decades, while the crisis also forced a rise in healthcare expenditure in the form of emergency treatment, testing, and vaccinations.

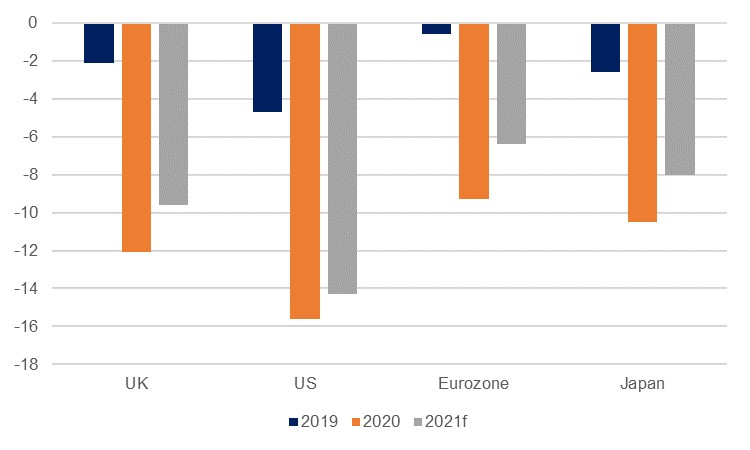

Source: Bloomberg, Emirates NBD Research

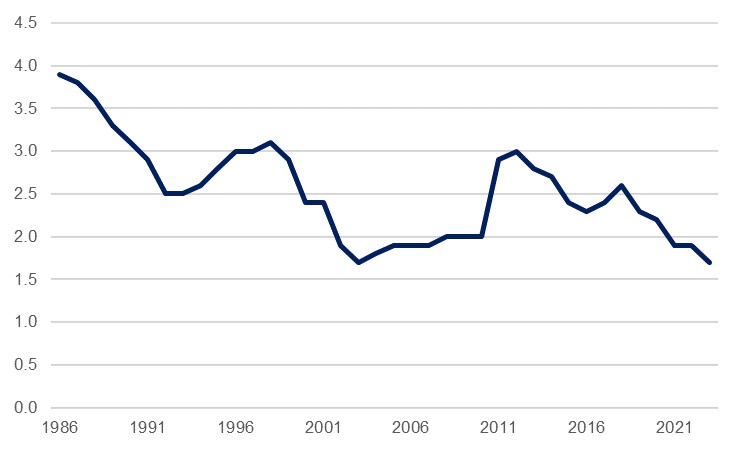

Source: Bloomberg, Emirates NBD Research

The net result has been a stark increase in budget deficits last year and as a proportion of GDP, the budget shortfall in the US rose from -4.7% of GDP in 2019 to -15.6%. While this was one of the larger expansions, the Eurozone, UK, and Japan also all saw their deficits go from the low single digits to -10% or more. Inevitably, this has also been accompanied by a massive expansion in public debt; in the UK, the debtload has exceeded total output for the first time since the early 1960s; in the US, debt has also climbed to greater than GDP, rising from 75% to 110%, a record high; in Germany, the government has put the convention of the debt brake on hold with its first budget deficits since 2011, borrowing more in 2020 than in any other year in the post-war period.

With the coronavirus crisis still ongoing – and the economic fallout likely to linger for some time beyond the last r-number headlines – developed markets are not about to pull the carpet from under the feet of the recovery just yet. Most notably this year we have had the sizeable American Rescue Plan signed off in March by US President Joe Biden, which includes an extension in support for those who have lost their jobs during the pandemic, in addition to the attention-grabbing direct payment of USD 1,400 to qualifying individuals, amongst other measures. In the UK, Chancellor of the Exchequer Rishi Sunak extended the country’s furlough scheme and brought in more support for the self-employed in his latest budget, while Germany plans to borrow an additional EUR 180bn this year, compared to the EUR 130.5bn seen in 2020.

Policymakers have been at pains to stress that they are conscious of the potential pressures this spending is putting on future finances, with Sunak telling the Financial Times that a one percentage point increase across all debt levels would result in an additional GBP 25bn a year spent on debt servicing. In the US, Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen told ABC News that ‘In the longer run, we need to get deficits under control to make sure that our fiscal situation is sustainable.’ Despite these statements, for the time being this remains an issue for down the line. Despite the reflation play that has driven yields on 10-year USTs back up to 1.72% earlier in March, the Fed and its chair, Jerome Powell, continue to push back against any near-term tightening of monetary policy, the ECB remains in negative territory and the BoE’s Bank Rate is at record lows.

Source: UK OBR, Emirates NBD Research

Source: UK OBR, Emirates NBD Research

The likelihood is that money in developed markets will remain cheap for some time and given that the bulk of government stimulus support has been financed directly by their central banks, this alleviates any immediate pressures on their finances. While debt levels as a proportion of GDP have risen to new highs, debt servicing costs are benign – in the UK just 1.9% of GDP, compared to 3.0% in 2011/12. Under these circumstances, policymakers will for now continue to focus on ensuring a durable economic recovery from the pandemic. Indeed, government support has been consciously sizeable this time around, contrary to the wide-held belief that government spending did not match the monetary measures taken during the GFC.

Once the fallout from the pandemic has eased, governments will start to look towards balancing their books, but this time around, the focus for the post-crisis future appears to be on raising taxes rather than on slashing spending through austerity programmes. In the US, the Biden administration is looking to follow up on its American Rescue Plan with a further USD 3tn multi-year infrastructure plan. The difference between the previous US spending pledges and the latest plan from the US, is that this will not be an ‘unpaid for’ package, and there are plans to increase taxes on corporations and wealthy individuals in order to fund it. These would represent the first major tax hikes since 1993, and while a wealth tax proposed by Senator Elizabeth Warren is unlikely to make progress, there is an apparent shift towards making the better-off pay more.

Meanwhile in the UK, there will be a ‘super-deduction’ tax reduction to encourage investment until 2023, at which point corporation tax will be hiked from 19% to 25%. This would entail a rejection of the Laffer Curve orthodoxies previously followed by Conservative governments, not least that under David Cameron which slashed corporation tax in the wake of the GFC. What is becoming increasingly clear is that the pandemic crisis has upended some long-held economic tenets, and over the coming years, government is likely to be ‘big’ in ways it hasn’t been for decades.