The barriers to earlier policy normalization by the Federal Reserve are falling thick and fast. With the renomination of Jerome Powell as Fed chair removing a somewhat political distraction from economic policy, we expect that the Fed will now focus squarely on addressing the elevated inflation pressures affecting the US economy. While getting the labour market back to levels near full employment will remain an important goal for the Fed, it appears to have more signs of being able to sustain itself without relying on rates being near zero. As a result, we now expect that the Fed will be able to begin raising rates next year, earlier than our prior assumption that rate hikes would begin in 2023.

The US economy is in far better shape than it was at the start of 2021 or even as recently as this past summer. After a few soft jobs reports in August and September, the US labour market moved into Q4 on a much stronger footing with 531k jobs added in October and those weaker numbers for Q3 revised upward. As it stands, the level of employees on non-farm payrolls is now 4.2m workers below its pre-pandemic peak. We expect that a large share of those 4.2mn workers off payrolls would have taken early retirement and many more will be reluctant to come back into the jobs market as perhaps a partner is working full time, likely at a higher wage level, or wealth effects have convinced them that they may be able to live off savings for some time.

Source: Bloomberg, Emirates NBD Research

Source: Bloomberg, Emirates NBD Research

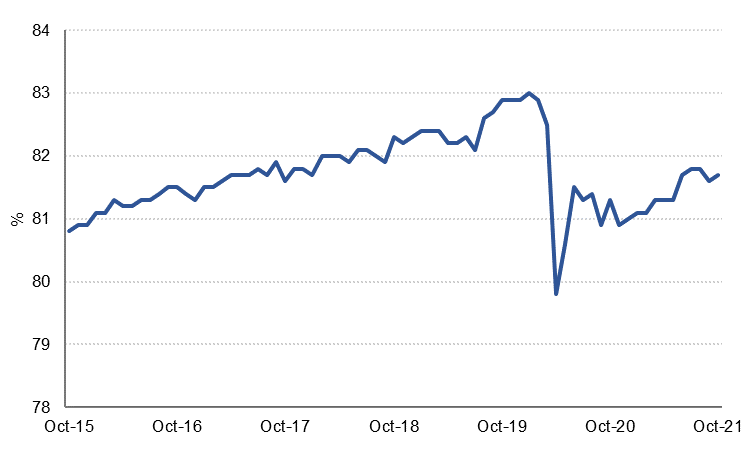

Fed commentary, in particularly in press conference following FOMC decisions, has focused on getting the participation rate of prime age workers back to pre-pandemic levels. But if the structural changes to the labour market hold—early retirements, more micro enterprises, staying at home for childcare or health concerns—then getting back to pre-pandemic levels may be the wrong target. Economists, including those at the Fed, are likely struggling with how to assess these fundamental changes to the labour market but the end result is that fewer people are likely to be part of the official labour force and thus achieving full employment, at least as measured by the U3 unemployment rate, may be easier. After peaking at nearly 15% in April last year the headline unemployment rate has fallen to 4.6% as of October, around 1 percentage point higher than it was in January 2020.

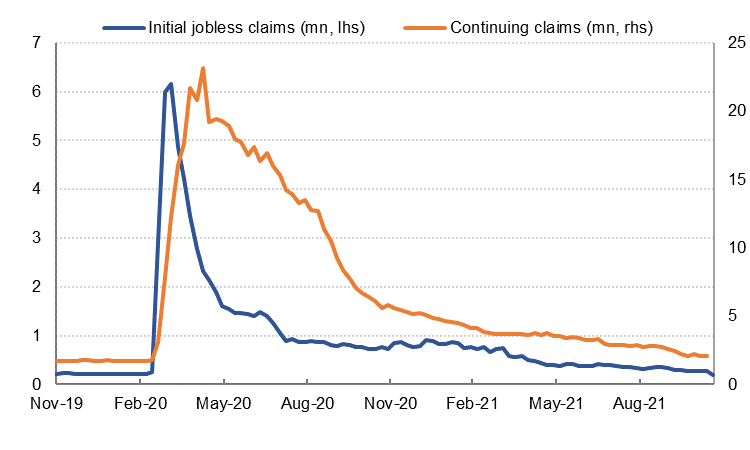

The US government has also issued vaccine mandates for federal government employees and also for private sector firms that employ more than 100 people. While the vaccine mandate for the private sector is currently encountering legal challenges and not presently being enforced, it should help to get more and more workers in the US covered by a Covid-19 vaccine and diminish health risks as a reason for staying on the sidelines of the labour market. Initial jobless claims have fallen by more than 130,000 since the beginning of October, and are at the lowest level since 1969. Continuing claims have also declined significantly over the last six weeks and are now only around 20% above their pre-pandemic levels.

Source: Bloomberg, Emirates NBD Research

Source: Bloomberg, Emirates NBD Research

The next labour market report is due on December 3rd and market expectations are for around 530k jobs to have been added in November. That would help to tick the headline unemployment rate down to 4.5% while average hourly earnings are expected at 5% y/y which would represent their strongest levels since low base effects in Q1 2020 helped to propel them higher earlier this year.

Provided that the labour market continues on course for sustained strength, the Fed can focus more squarely on inflation. CPI inflation rose by more than 6% in October, exceeding market expectations as high energy and food prices twinned with supply chain disruptions to push costs higher. While we are still of the view that many of the drivers of inflation in 2021—energy and food costs, reopening frictions—will dissipate in 2022, particularly in the second half of the year, there is a risk that core inflation will stay high as supply chain disruptions ease slowly.

The recent economic data – particularly on the labour market - confirms that the emergency support provided by the Fed last year is no longer necessary. The Fed has already moved to taper asset purchases, which at the current pace of reduction will come to an end in June 2022. At that point, the labour market may well be close to “maximum employment”, while inflation will likely still be significantly above the 2% goal, in the 3.5%-4.0% range. Consequently, we expect the Fed to raise rates in the middle of next year and then again in Q4, taking the upper bound of the Fed Funds rate to 0.75% by the end of 2022. We then expect a further 7 rate hikes over the course of 2023 and H1 2024, to 2.5%.

While some in the market are calling for a more aggressive hiking cycle, we are cognizant of several downside risks. The experience of Germany, Austria and other European economies at present shows that Covid-19 still presents a risk to public health and to growth and vaccine coverage in the US remains low compared with peer economies, with some parts of the country at vaccination rates below 50%. While we do not anticipate the US going back into lockdown, rising case numbers may again weigh on job growth over the winter.

Fiscal policy was a key contributor to strong consumer demand growth in 2021, with households sitting on an estimated USD 2.5tn in excess savings. While the Biden administration may still pass a sizable Build Back Better package before year-end, the impact of this will be spread over many years and will be financed partly by higher taxes, so the net impact on aggregate demand – and thus inflation – is likely to be much smaller than the fiscal support in 2020-21. Slowing inflation in H2 2022 for the reasons we’ve outlined here will also do much of the work for the Fed – real interest rates will increase faster than the rise in nominal rates as inflation and inflation expectations moderate.

The composition of Fed Board and the FOMC next year are also uncertain. With Lael Brainard promoted to vice chair of the Fed Board, there are three open spots on the Fed Board for President Biden to fill, with his nominations expected in the coming weeks. He has already made it clear that he wants to bring more diversity to the Board, and there is a possibility the Democratic nominees could tilt dovish. However, the regional Fed presidents who are voting in 2022 are considered more hawkish than the voting members this year.

In summary, we expect the improving labour market dynamics will see the Fed comfortable that its “maximum employment” mandate is achieved or close to being achieved by the middle of next year. With inflation likely to still be significantly higher than 2%, we expect the Fed to begin raising rates in mid-2022, and then again in Q4, sooner than we previously thought.