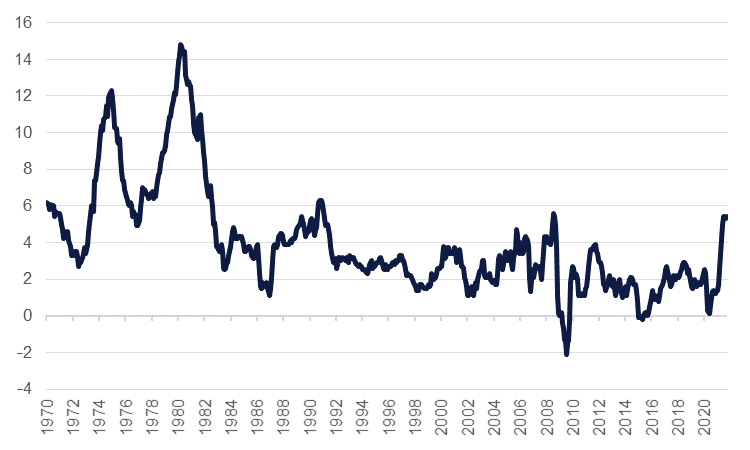

How the Federal Reserve responds to the jump in US inflation is the dominant question for financial markets. High commodity prices and reopening complications have contributed to higher headline inflation but may not lead to persistent gains in prices. A preemptive normalization of policy—via interest rates hikes—should help to cool inflation but could come at the cost of longer-term scarring in the labour market well after the initial shock from the Covid-19 pandemic.

Inflation in the US has been running at an elevated pace this year, with headline CPI rising by 5.4% y/y in September, holding at 5% or higher for the fifth month in a row. On a monthly basis the pace of growth picked up to 0.4% m/m compared with 0.3% a month earlier. When stripping out volatile food and energy costs, core CPI rose 4.0% y/y in September and advanced just 0.2% m/m, remaining well below highs of 0.9% seen earlier this year.

Source: Bloomberg, Emirates NBD Research

Source: Bloomberg, Emirates NBD Research

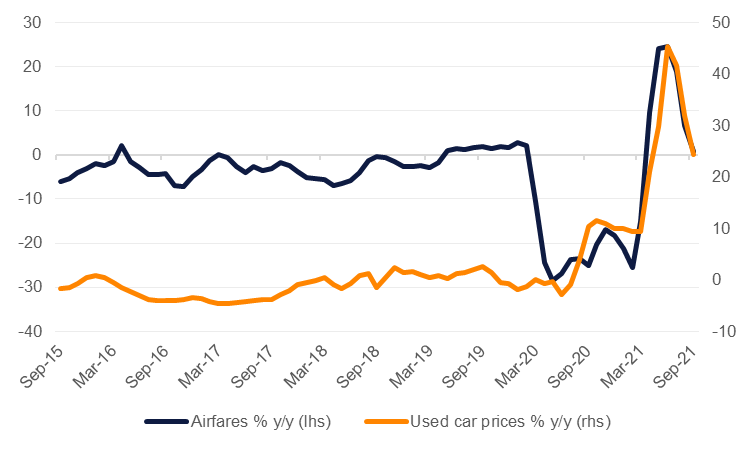

The fast inflation picture will clear the way for the Federal Reserve to begin its tapering of asset purchases, likely in November, even if much of the gains in the headline index are being driven by factors that we expect will fade in 2022. There have been three main drivers of the spike in US inflation this year: re-opening frictions as demand for services (airfares, hotels, dining out) and some goods (new and used cars) outstripped supply as restrictions on activity were lifted; energy and commodity price increases, again as demand surged while supply lagged; and supply chain disruptions which have led to shortages of products and components and also pushed up shipping costs exponentially.

We expect two out of three of these inflation drivers to moderate over the next nine to twelve months. Some of the re-opening related inflation has already started to dissipate – airfares declined m/m in July, August and September, used car prices have softened over the last two months as have hotel costs. We do not expect these components to contribute significantly to faster inflation next year.

Source: Bloomberg, Emirates NBD Research

Source: Bloomberg, Emirates NBD Research

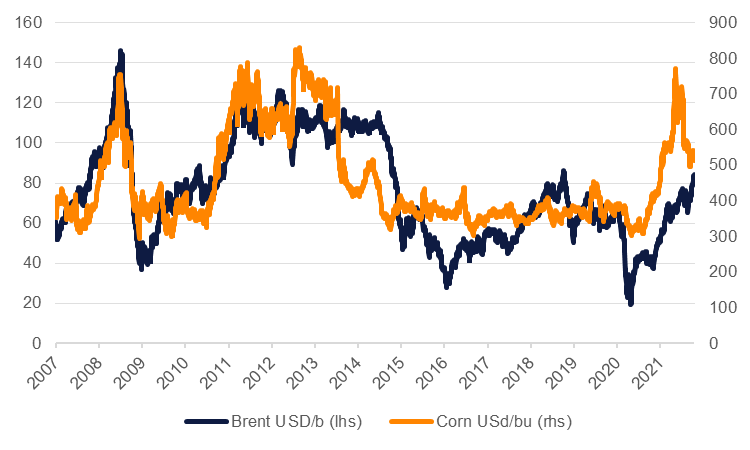

Energy costs are high across the board currently—particularly for natural gas and oil products—and will likely maintain an elevated level until at least the end of the year. But we expect a supply response from oil and gas producers in the US to be material and help to alleviate much of the current tightness in commodity markets. Along with increases in oil output from OPEC+ producers over the course of 2022, that should help to nullify the impact of energy keeping inflation high next year.

Source: Bloomberg, Emirates NBD Research

Source: Bloomberg, Emirates NBD Research

A similar situation plays out for food costs. Wholesale food prices are high at present—corn and wheat futures are up more than 30% y/y and 20% respectively as of mid-October—while the meats component of the CPI basket gained 10% in September, according the BLS. The USDA is projecting a build in global corn inventories during the next market year, which along with lower fuel prices should help to alleviate agricultural input costs. There are no doubt uncertainties related to weather conditions that can affect agriculture supply but consensus projections for corn, wheat and soybean prices are for a dip in 2022-23 from current levels.

The third key driver of inflation – supply chain disruption – is likely to remain a source of inflation well into 2022, however, as the spread of the delta variant in Asia has led to tighter restrictions on activity being imposed to safeguard public health. In some countries such as Vietnam this is necessary because of low levels of Covid-19 vaccination, while in other countries such as China it is due to a zero-tolerance approach by the authorities. The consequence is that manufacturing output and logistics services have been constrained by renewed lockdowns and other restrictions, which has had a knock-on impact on already strained global supply chains and higher producer inflation in other markets including the United States. Some of these higher costs are likely to be passed onto consumers in the coming months, although larger firms may be able to absorb some of the cost increase in favour of securing market share.

Consequently, while we expect headline inflation will slow from its current levels, it will be driven more by the ‘core’ components of the CPI. More troubling for the Fed we expect would be the pick-up in housing costs with rent rapidly recovering to its pre-pandemic level of growth after a substantial slowdown last year. Housing costs are not as easily traded away or avoided like other commodity expenditures and shelter accounts for nearly a third of the overall CPI basket.

Risk of core price growth staying high

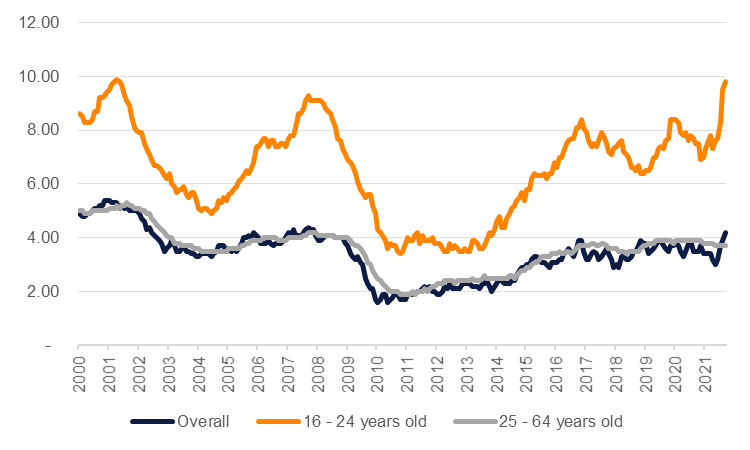

Were housing, rent and core input costs to remain elevated into 2022, consumers have limited options to redress them. One would be to demand higher wages: there is evidence of salaries moving higher with average hourly earnings up by an average of 0.4% m/m in the first nine months of 2021, almost twice the average annual pace seen in the five years prior to the pandemic. However, the Atlanta Fed’s wage growth tracker suggests that this year’s increase in wages has been most pronounced in the 16-24 year-old, low skilled, low wage level cohorts, rather than across the board.

Source: Bloomberg, Emirates NBD Research

Source: Bloomberg, Emirates NBD Research

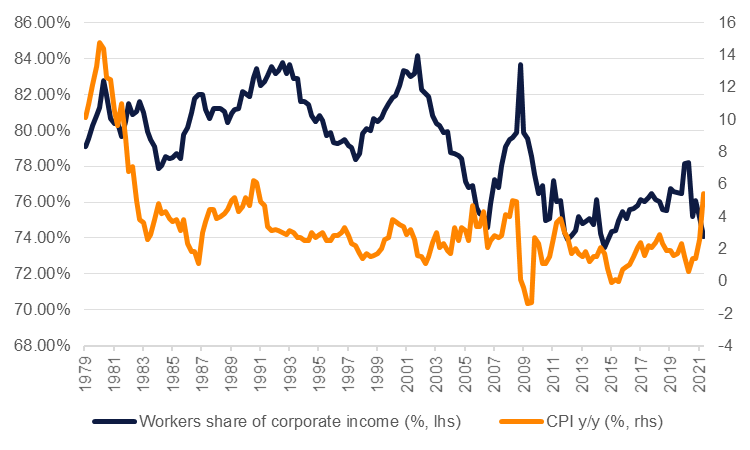

Some measure of wage hikes is overdue. Wages as a share of corporate income are near multi-decade lows, barring one-off spikes during recession periods. But with little restriction on firms passing through higher wage costs the risk of wages pushing prices higher is real.

Source: Economic Policy Institute, Emirates NBD Research

Source: Economic Policy Institute, Emirates NBD Research

Fed may need to choose one of its mandates over the other

Even as headline inflation decelerates in 2022, core components may prove stickier and force the Fed to make a choice to prioritise one element of its dual mandate: full employment or stable prices. Tackling the inflation issue via the normalization of policy—tapering of asset purchases or rate hikes next year—could add another drag to the economic recovery if firms face higher costs of capital and slow investment or hiring plans. That may actually end up alleviating the labour shortage by reducing the demand for workers but end up freezing out those who haven’t yet returned to the labour force. In other words, the unemployment rate may look attractive but largely because of workers exiting the labour force.

Conversely, keeping policy accommodative even as prices accelerate may not actually prompt workers back into the labour market. As noted in our podcast Discussing labour market frictions, there is a panoply of reasons keeping people out of the labour market in the US at present, not least of which is workers holding out for higher wages or because of wealth effects (which may be amplified further if the Fed keeps rates on hold).

The inflation dynamics in 2021 are generally a response to the impact of the Covid-19 pandemic and to our mind do not push against the long-term disinflationary trends at place in the US and indeed in most major economies: aging populations, spare capacity overhangs and digitization. See our note from January 2021 here.

Markets calling the Fed’s bluff

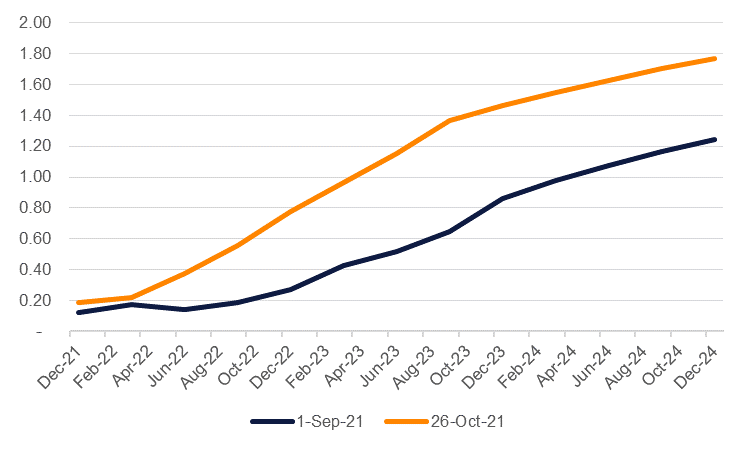

Markets have started to put money behind doubting the transitory inflation narrative trumpeted by the Fed and other central banks. The Eurodollar curve has shifted considerably higher since the September FOMC while UST yields near the front of the curve have shaken off the vagaries of debt ceiling negotiations and moved firmly higher in anticipation of a more aggressive rate trajectory: yields on 2yr USTs seem to be stable in a range of 0.35 - 0.45% while the 5yr has broke and stayed above 1%.

Source: Bloomberg, Emirates NBD Research

Source: Bloomberg, Emirates NBD Research

In our view, the two rate hikes next year currently priced in by markets may be too aggressive. If – as we believe – inflation slows sharply around the time the Fed comes to the end of its tapering in the middle of 2022, and the labour market has not yet reached full employment, then the Fed is likely to hold off raising rates for several months, possibly until early 2023. The key risk to this view is that inflation remains higher for longer than we currently expect, and that the Fed prioritises its price stability mandate and raises rates before the economy reaches maximum employment.