Notwithstanding last week’s decline in oil prices, the outlook for GCC budgets is much better than it was at the start of the year, following OPEC’s decision to curtail oil production for longer. In our note on 8 March, we argued that governments in the region would likely prioritise deficit reduction over increased spending to boost growth this year, and that lower oil production for longer would weigh on headline GDP growth in 2021.

As a result of a relatively conservative fiscal stance in the region over the last year – especially when compared with the largesse seen in the US, Japan and to a smaller extent Europe - we have maintained that the recovery in the non-oil sectors in the GCC economies this year would be largely driven by improving external conditions: the normalization of activity as vaccines are rolled out, recovery in global trade volumes, rebound in travel and tourism and increased investment.

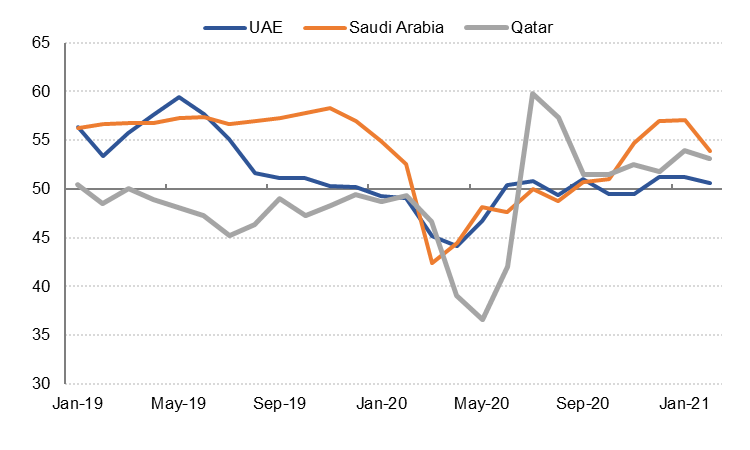

The PMI survey data indicated a slowdown in activity across the three biggest GCC economies in February as tighter restrictions were reimposed or extended in most major economies to curb the spread of the coronavirus. The UAE’s PMI averaged 50.9 over January-February, indicating very little expansion in the non-oil sectors at the start of the year. Firms appeared to be cautious about the outlook and this is likely weighing on private sector investment.

Source: IHS Markit, Emirates NBD Research

Source: IHS Markit, Emirates NBD Research

Moreover, the loss of private sector jobs since Q2 2020 has led to a decline in the expatriate population in the region. S&P Global Ratings estimates that the population of the GCC declined by -4% last year. For the UAE, the estimates range from -8% (S&P) to -10% (Oxford Economics). Official data on private school enrollments and active mobile phone subscriptions also point to a decline in the UAE’s population last year. This will likely have a negative impact on the speed with which GCC private sector consumption will rebound, particularly for countries where the majority of the population is expatriate, such as the UAE and Kuwait.

Reluctant to boost spending to drive growth and job creation, even with higher than expected oil prices this year, governments in the region have increasingly focused on structural reforms in order to attract investment and talent and boost domestic demand.

Earlier this month, Saudi Arabia enacted changes to its labour regulations to allow greater job mobility for expatriates, which could result in better alignment of salaries for foreign workers and Saudi nationals, and improve the attractiveness of the kingdom for more highly skilled employees. Saudi Arabia also announced that from 2024, it would only award contracts to companies that had their regional headquarters in the kingdom. While the specifics around this rule have yet to be clarified, it is aimed at requiring international firms to increase their investment – both financial and human capital - in the kingdom over the next three years. Saudi Arabia has pledged to continue developing the necessary infrastructure (education, healthcare, transport, leisure) to make the country a more attractive destination for foreign investment as well.

The UAE has announced several new and expanded visa schemes over the last year in an effort to attract and retain talent. The 10-year “golden visa” scheme was expanded to include a broader segment of the population, and new remote working visas and retirement visas were also introduced. Legislation to allow 100% foreign ownership of onshore companies was also passed, and is a key component of the recently announced industrial development strategy, which aims to double the size of the UAE’s manufacturing sector over the next decade, along with increasing research and development spending.

One of the key goals of the industrial development strategy is to create (skilled) jobs in the private sector which is essential for attracting and retaining talent, and boosting domestic demand. Importantly the strategy does not rely on a specific budgetary commitment from the government, but rather on creating the right environment through legislative reforms, providing incentives for investment, and providing financing to support SMEs in the industrial sector. However, we also recognize that structural reforms take time to implement and to yield results, and the eventual outcome will depend on how effectively the reforms and development strategies are executed.