There was little chance that the Federal Reserve was going to materially alter its policy stance at the April 30-May 1 FOMC meeting and in the event they kept the Fed Funds rate unchanged at 5.50% on the upper bound. Policymakers did acknowledge in the statement that there had been a “lack of further progress” toward the FOMC’s inflation targets as CPI and PCE prints so far this year have been running hotter than anticipated.

Source: Bloomberg, Emirates NBD Research.

Source: Bloomberg, Emirates NBD Research.

One notable shift in language in the statement was to describe the risks around reaching the Fed’s 2% inflation target “have moved toward better balance” rather than “moving into better balance” in its previous statement. That seems to be an acceptance that the next several inflation prints could again disappoint on the upside, particularly as gasoline prices could hold near their current levels and mean that the dampening effect on inflation from energy prices at best goes flat or at worst starts to contribute more meaningfully to upside inflation pressures.

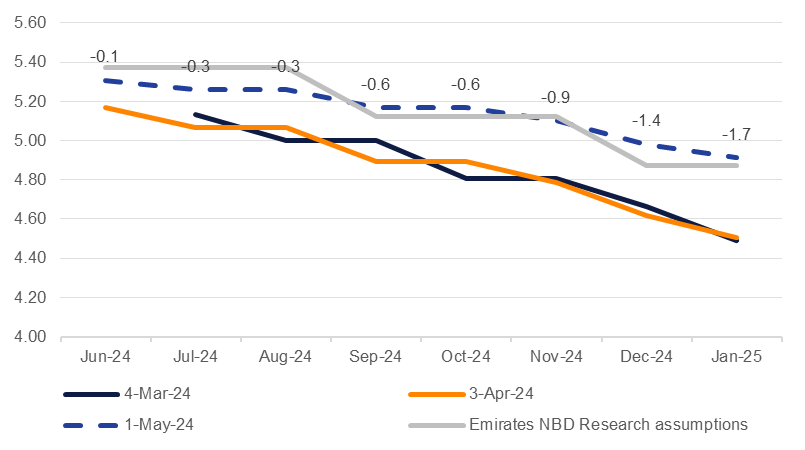

We adjusted our expectations in mid-April for when the Fed would begin to cut rates to two 25bps cuts, in September and December, and are holding to that view. We highlight risks to the upside on rates (ie fewer or no cuts) if inflation substantially disappoints to the upside at the same time as activity or labour market indicators show few signs of softening.

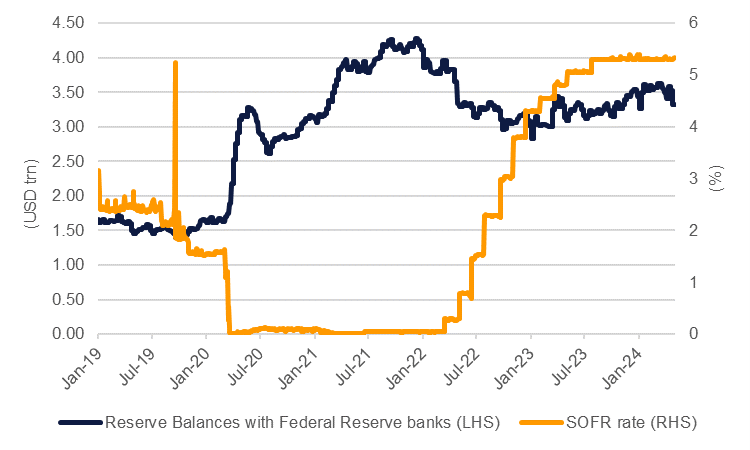

To perhaps offset the impact of keeping a restrictive stance for longer, the Fed did announce it would taper the pace of its balance sheet rundown by reducing the monthly redemption cap on US Treasuries to USD 25bn from USD 60bn. The FOMC will keep in place its rundown of mortgage-backed securities at USD 35bn/month and will reinvest any payments above that level into USTs. The tempering of quantitative tightening is in line with the Fed’s objective of maintaining ample reserves in the banking system to avoid strains seen in repo markets when the Fed was undertaking QT prior to the pandemic.

Source: Bloomberg, Emirates NBD Research.

Source: Bloomberg, Emirates NBD Research.