China’s Q3 real GDP growth results, which disappointed to the downside in data released today, are potentially a foretaste of more disappointing Q3 data to come, especially from those countries that have been pursuing a zero-Covid strategy. When combined with ongoing supply chain issues, and the energy crunch which began to make itself felt during the period, the headwinds to global growth have been mounting. While the expectation remains that the global economic environment will improve as the pandemic pressures ease, the fallout from its economic disruption will remain a challenge for some time to come and these trends will remain in play through the final quarter of the year.

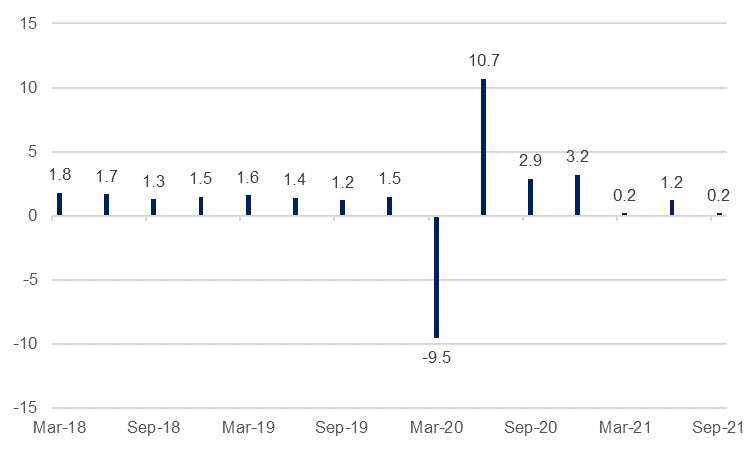

The first major economy to announce its third quarter growth statistics, China recorded real GDP growth of 0.2% q/q in Q3, missing expectations of 0.4% growth, and down from 1.3% in Q2. On a y/y basis growth was 4.9%, which given the relative containment of the virus within China in 2020 compared to many other countries (y/y growth was positive in Q3 2020, meaning reopening base effects from an economic contraction are not in play to the same degree as elsewhere) is a relatively quick pace. Nevertheless, this too missed consensus projections of 5.0% and was down from 7.9% in Q2.

Source: Bloomberg, Emirates NBD Research

Source: Bloomberg, Emirates NBD Research

Some of the factors driving the slowdown are unique to China, not least the government’s newly invigorated pursuit of ‘common prosperity’ and the fallout from that on various sectors, most notably construction and real estate: property investment ytd is up by a robust 8.8% y/y, but this is down from 10.9% at the close of Q2 and missed projections of 9.5%. Fixed asset investment rose 7.3%, missing consensus 7.8%. However, other factors which weighed on growth in China are likely to have also impacted other countries as they start to report their Q3 results, and will continue to exert a drag globally in the final quarter of the year.

Chinese industrial production missed projections in August and September as the global energy crunch which has seen gas prices in Europe skyrocket and Brent crude hit three-year highs at nearly USD 86/b took effect. Factories in many provinces have been forced to reduce activity, operate at night when demand on the grid is less, or cease production altogether. This has played out in other major economies also, for instance the rising gas prices forced CO2-producing firms in the UK to stop activity in September, with knock-on effects on the food industry, while other heavy industry sectors have warned the British government that they will need greater support if they are to maintain output. With this global phenomenon only strengthening as it goes on, higher energy prices will exert an even greater drag on growth in Q4 than seen in Q3.

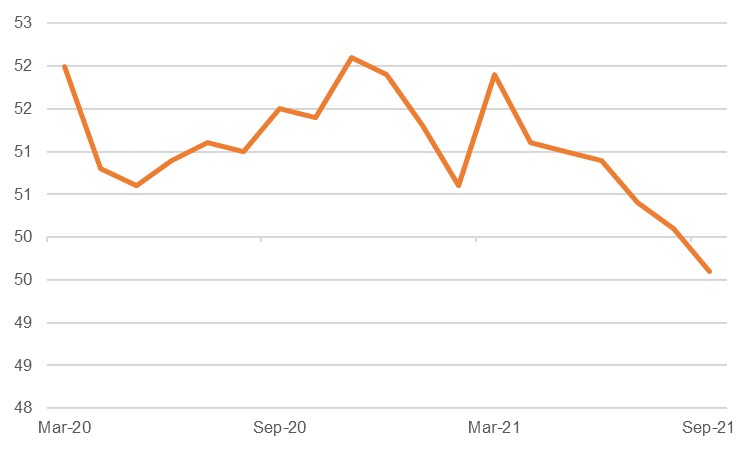

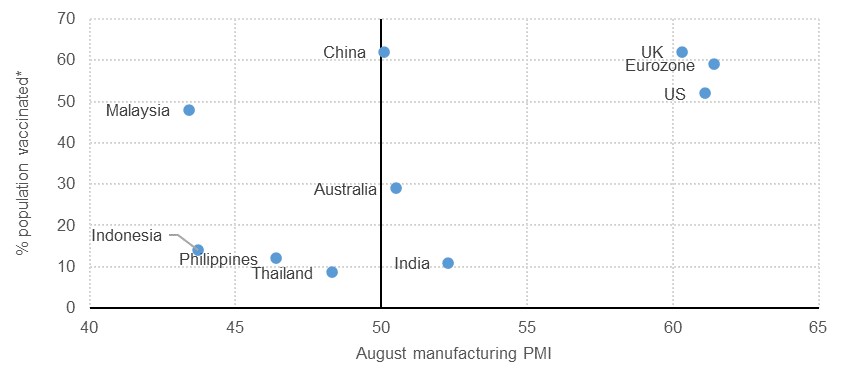

The ongoing Covid-19 crisis also arguably weighed on Chinese production in the third quarter. Despite comparatively high vaccination levels the Chinese government has pursued a zero-Covid strategy, and new outbreaks and associated restrictions held back activity in Q3. For instance, Japanese car firm Honda was forced to suspend its operations in Wuhan in August as workers were unable to come to work. This contributed to China’s manufacturing PMI falling back to 50.1 that month, the lowest levels since the Covid-driven 35.7 in February 2020. In September the index dipped back below 50.0 to 49.6.

Source: Bloomberg, Emirates NBD Research

Source: Bloomberg, Emirates NBD Research

This is a trend we are likely to see weigh on Q3 growth figures from other Asian economies that have been seeking to completely contain the pandemic, with Indonesia, Malaysia, Philippines and Thailand’s PMIs all slipping well below the neutral 50.0 level in August as they contended with their own Covid outbreaks. And it is worth noting that it is not only developing nations that have been pursuing this strategy – Australia has had an especially stringent lockdown in place over the course of 2021, which will have weighed on private consumption there, while the New Zealand central bank’s plans to hike interest rates in August were derailed by the discovery of one positive Covid-19 result. Direct coronavirus pressures do seem to be easing globally, but the IMF has highlighted the persistent danger of new variants taking hold in countries with lower levels of vaccinations, and the deleterious effect that could have on future global growth.

Source: Bloomberg, Emirates NBD Research

Source: Bloomberg, Emirates NBD Research

One notable positive in the Chinese data released in October was export data which expanded 28.1% y/y in September in dollar terms, meaning an average growth rate of 24.3% over Q3, even as some of those aforementioned challenges took hold. Indeed, China in fact benefited from some of the lockdowns seen in those Southeast Asian economies, as production shifted there. However, this does not necessarily translate to an entirely positive indicator for other countries’ upcoming GDP growth results, even if it is evidence of still robust demand.

Source: Bloomberg, Emirates NBD Research

Source: Bloomberg, Emirates NBD Research

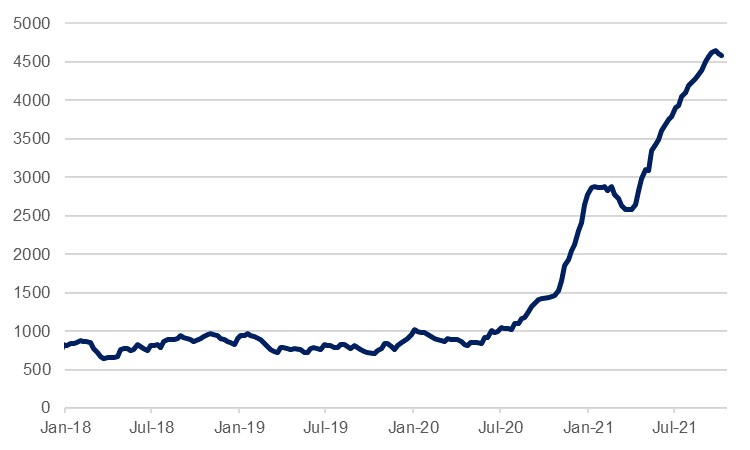

For starters, some of that strong growth in exports is attributed to rising prices rather than higher output, meaning that inflationary pressures will continue to pass through to producers and consumers in developed market economies to varying degrees. Further, the effect of this surge in exports will continue to exert pressure on overladen supply chains; the Shanghai Conainerised Freight Index has dipped modestly over the past two weeks but remains over four and a half times higher than it was in pre-pandemic January 2020 as demand for shipping services far outstrips supply. These higher shipping prices and general disruption have been noted in respondents to PMI surveys in the Middle East, US and Europe as holding back their output for months now and are unlikely to alleviate to any marked degree before year-end given the amplifying bullwhip effect.

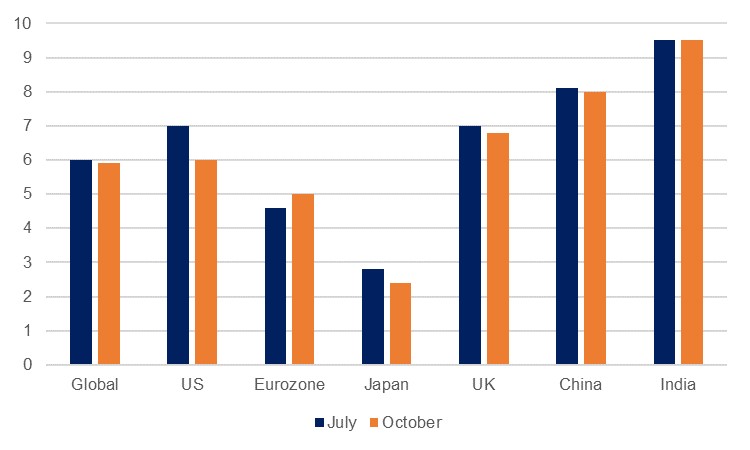

Source: IMF, Emirates NBD Research

Source: IMF, Emirates NBD Research

While the IMF only downgraded its global growth forecast for 2021 by one basis point this month (5.9% compared to 6.0%) and left 2022 unchanged at 4.9%, it made clear that supply chain disruptions were a major threat to global growth, and the sizeable downgrades for the US and Germany were largely predicated on the back of this. It is worth noting also that an underperforming China would still hold back global growth even if some of these pressures eased in DMs. The second largest economy in the world, it is also a major importer of raw materials, with the outlook for a host of EM commodity exporters dependent on it for instance. As such, it is always worthwhile to parse the Chinese GDP data for indications of the global outlook.